Mali’s arrest of Barrick employees shows continued push for sovereignty in West Africa

Transnational mining interests have long benefitted from Mali’s mineral wealth

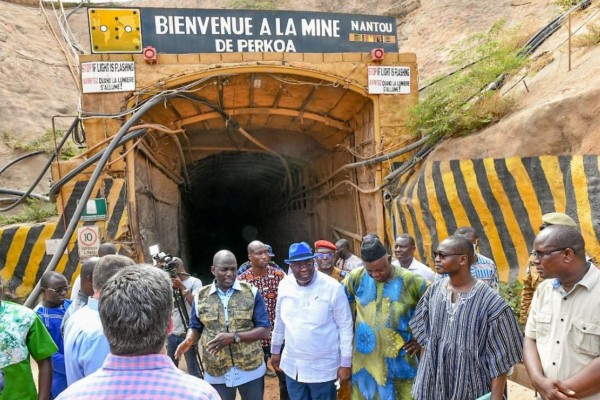

The Malian government under Colonel Assimi Goïta, pictured here, is demanding Resolute Mining and Barrick Gold pay hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes and fines.

In the past few months, the government of Mali took new steps to challenge Western mining interests and increase the state’s share of profits from the industry. Its targets were Resolute Mining, an Australian firm that raked in revenues of $341.5 million in the first half of 2024, and Canadian mining giant Barrick Gold, whose third quarter revenues this year totalled $3.37 billion.

Transnational mining interests have long benefitted from Mali’s mineral wealth, but in the country itself, life remains extremely difficult. Mali has some of the highest poverty rates in the world, while an Islamist insurgency in the north, which the Ukrainian government claims it is supporting, has killed thousands and displaced hundreds of thousands. In this challenging context, the Malian government under Colonel Assimi Goïta (who has been interim president of Mali since 2021) recently detained four Barrick employees and three employees of Resolute, including the latter’s chief executive Terence Holohan.

Chris Eger, Resolute’s chief financial officer, described Mali’s efforts to increase state revenues from mining as “unfortunate.” He added: “We’re seeing it across Africa, especially in West Africa. It’s unfortunately the environment that we’re living in… people are looking for possibly a bigger piece of the pie.” For his part, Barrick Gold CEO Mark Bristow described the detention of Barrick employees as “unjust” and stated that “efforts to find a mutually acceptable solution [between Barrick and Mali] have so far been unsuccessful.”

The Malian government is demanding Resolute and Barrick pay hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes and fines. Resolute has agreed to cough up the $162 million in back taxes that it owes the Malian government, while Barrick is resisting Mali’s efforts to collect over $500 million in unpaid taxes and dividends from the company.

The dispute between Mali and Barrick did not begin with the arrests. The two have been at odds since Mali passed its new mining code, which increased the state’s role in the sector, in August of last year. Barrick opposed the reform, with a company spokesperson noting that the new code represented a “difference of opinion” between Barrick and Mali. Barrick rejected a subsequent mining audit, which aimed to collect hundreds of millions from foreign mining companies, as “legally and factually flawed and without merit.”

As discord grew in early 2024, Bristow demeaned Malians, claiming “We’re dealing with people that are not particularly competent in the mining industry.” He warned the West African country: “Be careful you don’t compromise the benefits to Mali by taking too much.”

From the perspective of the Malian government, it is Barrick that was “taken too much” by refusing to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes and fines. In response, Mali arrested four Barrick employees in October, releasing them shortly thereafter. The company continues to resist Mali’s demands, and as a result, the employees were arrested once again on November 26. Barrick responded with a press release refuting the charges.

Mali’s efforts to restructure mining agreements, challenge the predominance of Western companies, and increase the state’s role in national development are linked to a growing anti-imperialist, pan-Africanist movement in the region. This wave of resistance has seen the Alliance of Sahel States (Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, also known as AES) expel French and US troops, revise mining codes tilted in favour of foreign investors, and nationalize critical natural resources including gold, water, and uranium. It has seen Chad and Senegal sideline the French military. It has seen Senegal and the Ivory Coast revise their mining sectors to increase state revenues. And it has seen West African states, namely the AES, challenge the Canadian mining companies that have long benefitted from neoliberal investment regimes on the continent.

AES governments enjoy wide popular support, with many Africans viewing the alliance’s push for sovereign development and economic integration as a new phase of pan-Africanist struggle. Indeed, these three countries withstood sanctions from neighbours, coup attempts, continued French interference, and war against Islamist insurgencies.

Meanwhile, pan-Africanist policies promoting broad-based, inclusive development are growing in popularity across the region. Burkina Faso’s leader Ibrahim Traoré frequently invokes the legacy of Thomas Sankara in his speeches, while Mali’s Goïta has vowed to “resolutely follow the path laid out 64 years ago” by Modibo Keita, a socialist and Mali’s first post-independence president. In Niger, the government is renaming streets and squares that once honoured Frenchmen to instead recognize African liberation fighters. A boulevard in Niamey named for Charles de Gaulle has been renamed in honour of Djibo Bakary, a socialist politician who fought for Niger’s independence from France. A stone portrait of French commander Parfait-Louis Monteil has been replaced by a portrait of Sankara. “Francophonie Square” is now “Alliance of Sahel States Square.”

One important element in this new phase of pan-Africanist struggle is the fight against foreign mining companies. West Africa is a mineral-rich region, and leaders from Traoré to Goïta to Senegal’s Bassirou Diomaye Faye recognize that greater state control of the industry is a necessary precondition for sovereign development.

As the region continues its push for sovereignty, we can expect Canadian mining companies to grow more intransigent—and as a result, we should anticipate more conflicts like the one between Mali and Barrick Gold.

Owen Schalk is a writer from rural Manitoba. He is the author of Canada in Afghanistan: A story of military, diplomatic, political and media failure, 2003-2023 and the co-author of Canada’s Long Fight Against Democracy with Yves Engler.