Locals pay the price of super gentrification in Mexico City

It’s easy to understand the escalating local anger toward the attitudes of some remote workers living in CDMX

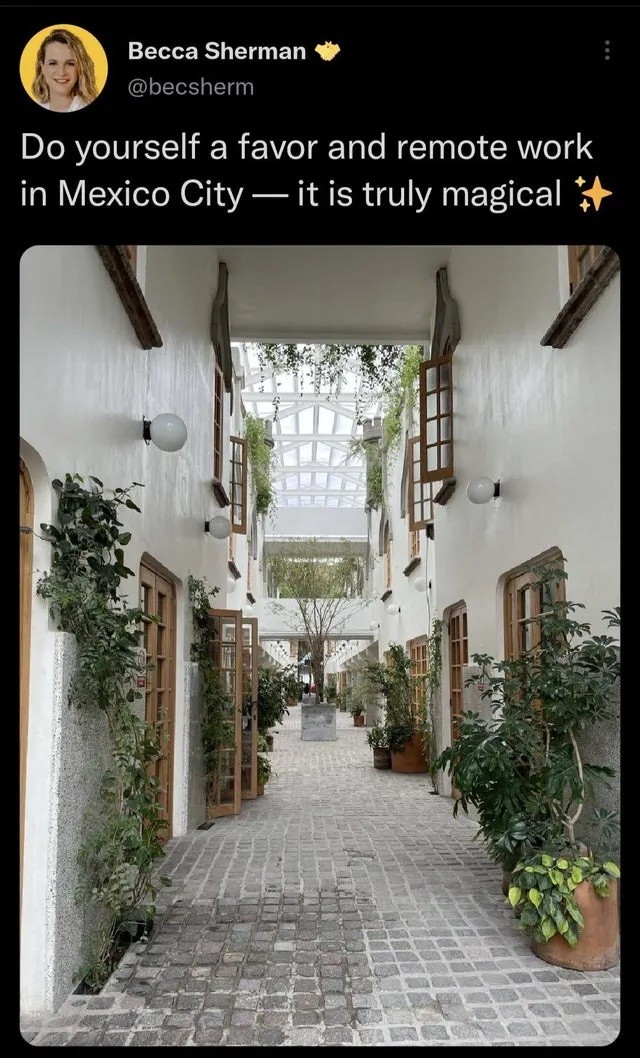

La Roma Norte, Ciudad de México. Photo by Natch Jarero/Flickr.

The accelerated gentrification of two of Mexico City’s neighbourhoods, La Condesa and La Roma Norte, has caused tensions and a near-impossible living situation for local Mexicans. The already trendy neighbourhoods, accustomed to the presence of foreigners and their money, have undergone a process of “super gentrification” since the beginning of the pandemic, exacerbating rising housing costs and sending prices soaring above inflation rates.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a particularly cruel impact on locals in some of Mexico City’s central boroughs. It has amplified tensions between long-term Mexican residents and newcomers from the north, culminating in a protest on November 17, 2022, when the streets filled with locals carrying signs with slogans urging remote workers and digital nomads to return home.

On October 26, a few weeks before the protest, the municipal administration in Mexico City struck an agreement with Airbnb and UNESCO allowing the short-term accommodation rental platform to operate within the city with fewer restrictions. While the details of the agreement have mostly been kept confidential, the platform will now incentivize remote workers by offering discounts for longer-term stays.

Even prior to the agreement, the city was under pressure with the onset of the pandemic and the extensive shift to remote work; remote workers, mostly from the tech sector, descended on the city in search of cheap rent. Entire buildings were bought and sold to serve as short-term accommodations. The tenants evicted in the process were forced to move to the outskirts of town. “Silent evictions” have become common practice as renters are told by landlords that their contracts will not be renewed. One renter offered to pay a rent increase and was refused on the grounds that the view from her apartment was an important asset for Airbnb.

Rents for apartments in these central neighbourhoods are listed as high as $1,500 per month, in a country where the minimum wage in the formal economy is generally $8 per day. In Mexico City, there are four centrally-located districts that account for 53 percent of the jobs, although they are home to only 19 percent of the population. Due to their move to the outskirts, workers are now spending more of their time commuting to the centre for work, often labouring in economic sectors that cater to tourists and the remote workers living there.

There is a notable difference, however, between the digital nomad and the remote worker. The digital nomad is a freelancer who has traded in the possibility of a high income in a corporate environment for a more meaningful and relaxed lifestyle in a sunnier and friendlier country. Remote workers, by contrast, are usually corporate tech workers earning salaries in US dollars, often exceeding $100,000 per year, who are now in a position to travel thanks to the pandemic-accelerated shift to working remotely. While both categories of travelers contribute to gentrification, remote workers are more responsible for driving up costs in Mexico City since 2020. A new wave of gentrification has begun, and the remote worker’s purchasing power is the main attraction for local governments and short-term rental platforms.

There are 800,000 American-born immigrants currently living in Mexico—a number that does not include travelers or people without visas. An American can legally live in the country for up to 180 days without a visa. Tourism accounts for 17 percent of Mexico’s GDP—a percentage second only to Thailand among developing countries. Their lack of sensitivity to the plight of the locals notwithstanding, nomads and remote workers are not entirely to blame for super gentrification, which stems from a broader process rooted in colonialism.

Máximo Ernesto Jaramillo, an activist in Mexico City, describes the financialization of housing as the treatment of shelter as a commodity and an asset rather than a home. During the November protest, Jaramillo stated that “for large companies, supported by the authorities, housing is no longer important as a place to live, but as a financial asset.” Financialization used to target home ownership but is now finding a market in rental properties. In the case of developing countries, the opportunity lies in attracting remote workers.

When Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum promoted the agreement between Airbnb and UNESCO as an effort to publicize the city as a “digital tourist centre,” she omitted to mention the adverse consequences of this type of deal. In fact, according to El País, she denied that the sudden increase in housing prices were due to Airbnb operations. Yet a study by her own government showed that the number of temporary homes in the city centre more than tripled between 2000 and 2022, from 22,122 to 71,780. For instance, in Cuauhtémoc, a borough in the centre founded by the Aztecs in 1521 and home to their sacred Tenochtitlan, more than 10,000 homes have already been designated as temporary.

While they haven’t made the details of the agreement known to the public, Airbnb noted in a recent report to their investors that bookings in the city had increased by 33 percent in the last three months. It is inconceivable that this kind of growth would not have fuelled skyrocketing rental prices.

According to Fabiola Mancinelli, assistant professor of anthropology at the Universitat de Barcelona, digital nomadism is a creative solution to the problems of young workers in the Global North. Faced with housing crises in Canada, the United States, and Western Europe, young people take up residence in the South in search of an enjoyable and affordable life by whatever means they can. Governments and corporations contrive the systemic inequities that displace one group while making room for another. While the local residents of a few neighbourhoods in Mexico City may experience some of the most brutal consequences of super gentrification, it is a global system of housing collapse that lies at the root.

But the financialization of housing and the inequitable costs of living for the residents could be resolved by government regulation. It’s a matter of political will as there are measures that governments in both the North and the South could take to curb gentrification: limiting the presence and power of short-term rental agencies, stopping the practice of silent evictions, extending rent controls, discouraging short-term accommodations, and investing in affordable housing.

Kimberly Wilson is a member of Canadian Dimension’s coordinating committee. Kim currently works as a community literacy worker in Toronto’s West End. She is a freelance editor and writer and holds a Master of Arts in Canadian Studies and Indigenous Studies from Trent University.