Latino Mercenaries for Bush

In the faculty dining room at the California State University where I teach, a Mexican-American woman places the thin slice of turkey on the bread to make my sandwich. The stress lines that radiate down from her high cheekbones twitch as she tells me politely that she’s fine. One of her sons is in Afghanistan, she reports. The other will leave tomorrow for Iraq. “I pray every day,” she says, smearing the mayonnaise on the other slice of bread.

“Why did the kids join the military?”

“The older joined the National Guard,” she informs me, with still a trace of an accent. “He thought he wouldn’t see real action. The other one just wanted to fight overseas.” She smiles, resigned to her lack of control over adolescents growing up in a combat culture. “He’s a good boy, but believes what the whatcha-call-‘em guys told him - you know, the ones that look for kids to join up?”

I ask how she feels.

“I ask God to return them to me,” she says. “Do you think they’ll be alright?”

“I hope they will,” I say. “But I don’t know.”

“What can I do to bring them home? I’m desperate.”

Desperation describes the mood of hundreds of thousands of Latino parents whose kids serve in the war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq. It also describes the current behaviour of the rich and confident managers of the U.S. empire, who, in less than three years, have gotten almost 200,000 young men and women stuck in two quagmires without an exit strategy.

Not Enough Troops to Occupy Two Places

Bush’s Middle East wars and the subsequent occupation of large countries by the U.S. military and the National Guard have not only divided the nation and fomented deep anti-American sentiment throughout the world; they have also strained the resources of the mighty Pentagon. The 2005-06 “Defence Budget” of $640-billion-plus (counting the intelligence budget) comes to almost twice what the rest of the world spends on “defence.”

Until the 21st-century Middle East wars, the military casually filled its recruiting quota from amongst poor youth around the country. National Guard service appeared attractive, since the chances of having ever to engage in an actual war seemed remote to hundreds of thousands of volunteers.

That all changed quickly after Bush invaded Afghanistan and Iraq, and discovered that he did not have enough troops to occupy both places. So, he called up the Guard and launched an aggressive recruiting campaign. But news of the growing count of dead and wounded filtered through the administration’s optimistic spin, and even the least informed and usually gullible teenagers began to think twice about “joining up.”

In order to get the young flesh “to serve” without the draft in the almost two-million-strong armed forces, the Pentagon raised salaries and increased benefits. From top to bottom, military salaries jumped between three and four times in less than 20 years. In 1981, a private, the lowest rank, earned less than $4,500 a year. Today that same rank comes with a salary of almost $15,000. A corporal, two short grades up, leaped from $5,000 to $22,000. In addition, he or she gets free food, housing and clothing - uniform - and discounts on most consumer goods.

Officers, many without post-graduate levels of formal education, can earn up to $125,000 and enjoy the privileges of elite clubs, like ski resorts in the Alps, and have private jets at their service. High-ranking officers have servants and other perks. For the first time in its history, the United States has a large, standing professional army.

Teens No Longer Falling for Recruiter’s Line

Yet, in 2003, despite increases in salaries, bonuses and other promises of free education and training offered by the armed forces, the recruiters fell short of their quotas. The once-easily gulled teenagers who fell for the slogan “Be all you can be in the Army” began to feel the sway of opposite stories, of how friends and family members got killed or permanently disabled by IEDs (improvised explosive devices). The body count and the number of wounded kept rising. By mid-October, almost 2,000 U.S. servicemen and women had died, with estimates of more than 20,000 wounded.

“As dimwitted as American teenagers are,” a Mexican-American army recruiter confessed to me in June in Pomona, California, “they’re not stupid enough to fall for the crap we’re selling to get them to go to Iraq or Afghanistan. Don’t quote me.”

I’m quoting him, but omitting his name and rank. His parents came from Sinaloa and settled in San Bernardino, where he grew up and decided to make an Army career after he dropped out of high school. “It pays okay and I don’t work too hard. I’d rather be here than in Iraq or Afghanistan. I’ll tell you that.”

Next to his recruiting table outside the university student centre, some undergraduates had set up a “de-cruiting” table offering prospective recruits “the facts about the U.S. military,” including the numbers of dead and wounded that the two wars had already exacted. In addition, the anti-military students “clarified” some of the Army’s offers of big loans and other supposed benefits, which they claimed were far less than the military promised. They had statements from some returning wounded veterans to the effect that the Army had docked their pay and cut their benefits.

Looking South for Soldiers

Faced with shortages of manpower, the ever-inventive Pentagon began to look abroad for fresh meat to send to Iraq. The closest neighbours to the south make an ideal recruitment arena - widespread poverty and unemployment. The armed forces offer citizenship to “illegals” who enlist.

In addition, young Latin American men will cost the Pentagon much less than homegrown soldiers, just as they do when they work in the maquilas (foreign-owned factories that produce goods mainly for the U.S. market) rather than in U.S. factories.

Like the maquila owners, who engage contractors to find them workers for their factories, the Pentagon also hires companies - American ones, of course - to find “outsourced mercenaries” for the Iraq occupation. Like the outsourcing of other jobs, Third World people take positions once held by Americans at much lower wages - but higher than they could make at home.

For “illegal” Mexicans, or those who want a quick route to citizenship, the military holds a strong attraction. Since Mexico provides the closest and most logical recruiting arena, Mexican “illegals” numerically outstrip all other Latin Americans living in the United States - and in Iraq itself. Some 8,000 Mexicans have now volunteered for official military service.

Mexicans and those of Mexican descent make up more than half of the approximately 110,000 Latinos (the rest mostly Puerto Ricans, Dominicans and Central Americans) currently serving in the U.S. military. In addition, almost 25,000 more Mexicans have enlisted as a means of obtaining U.S. citizenship. “Coyotes” smuggled some of these Mexicans - who never had any “legal” documents - into the country as children.

The recruiters target high schools with heavy populations of Mexican descent. The Marines have had particular success in their forceful publicity campaign. They claim that youth of Mexican origin make up 13 per cent of the Corps. But that high percentage of Latinos also shows up in the high dead and wounded count.

Outsourcing the War

If U.S. corporations can outsource jobs, why can’t the Pentagon outsource war? For much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, U.S. troops invaded Latin America. Indeed, not one country in the hemisphere has escaped the presence of uninvited U.S. troops. Now, the United States recruits Latin American troops to train in its homeland bases and then ship to the Middle East.

In late February, Salvadoran President Elias Antonio Saca unashamedly welcomed “his heroes,” a unit of soldiers returning from Iraq. Then he thanked President Bush while school kids recruited for the ceremony waved flags - U.S. and Salvadoran.

These “coalition of the willing” troops represented the pay-off for bribes offered by Washington to the rest of Latin America. Most presidents did not bite. But those in Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama did offer token forces. But most of the willing became unwilling when the occupation of Iraq turned into a sticky situation and the elaborate promises made by Bush didn’t materialize. El Salvador, with some 340 soldiers troops left in Iraq, is the only Latin American country to remain in the coalition.

As most other nations withdrew their troops, and as U.S. National Guard members began serving longer tours of duty (much to the dismay of their families), recruiters found El Salvador a fertile recruiting ground.

Recruiting Across Latin America

By paying Latino Americans trained in firearms and other repressive skills up to $3,000 a month, the Pentagon’s private recruiting companies flesh out its ranks in Iraq. They’re “having no problem finding recruits,” said Dan Broidy, author of The Halliburton Agenda: The Politics of Oil and Money. He estimates the United States has hired more than one private security professional for every ten American soldiers in Iraq.

Contractors and even subcontractors have also recruited in Chile, Colombia, Nicaragua and Guatemala. Because these countries have all trained huge numbers of young men in the “science” of killing, and other police and military-related activities, they make ideal pools for Iraq headhunters.

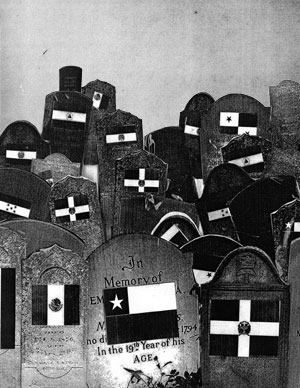

But in May, 2003, no one expected to outsource the war. Indeed, the White House heavies expected Iraqis to throw kisses and flowers at them - not a prolonged occupation that turned into a mass graveyard and mutilation arena for U.S. servicemen and women. Bush’s triumphal “Mission Accomplished” speech on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln did not prepare the nation for the sobering facts that gradually began to leak into the media.

Even before the bloody November, 2004 battle of Fallujah, which exacted a heavy toll, Mexican families began to feel the pain of war. The dead, and the legless, armless, eyeless and brain-dead wounded, began to come home. On both sides of the Rio Grande, Mexican parents shared a common anguish.

One hundred and twenty-two Latinos were among the first 1,000 U.S. casualties in Iraq. Seventy of them were of Mexican descent.

Mercenaries Wanted

Far from the recruiting tables on high-school and college campuses, Internet ads and word of mouth through military and ex-military clubs have led to the recruitment of Colombian gunmen for work in Iraq. The Internet is loaded with such opportunities - like this one from Hostile Control Tactics LLC of Fairfax, Virginia: “We are seeking talented individuals willing and capable of working as a Protective Security Specialist in a high risk environment. (Must be willing to deploy to Iraq or Afghanistan for 3mo., 6mo., and up to 1 year). Immediate Openings, Effective in September 2005 APPLY VIA OUR WEBSITE www.hctactics.com Skills required: Individuals with prior military, law enforcement and close protection/bodyguarding experience preferred.”

Another ad - on www.iraqijobcenter.com - tells job seekers: “Your New career in IRAQ starts here. Posting your resume on Iraqi Job Center, you are taking the first step to a great new career! Post your profile and resume for FREE and find the perfect job!”

On May 15, in the “Jobs Wanted” section of Epi Security and Investigation Company’s website, Pedro Buenaño of Ecuador described himself as “Mercenary, payed [sic] killer.” He would accept work in Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and, of course, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Epi is based in Manta, Ecuador, and is managed by Jeffrey Shippy, a U.S. citizen. In the case of iraqijobcenter.com, its website claims that it “is owned and run by the private Dutch company NOURAS. Iraqi job center offers its service for free for job seekers and employers.”

According to Pascale Mariani and Roméo Langlois, writing in the August 26, 2005 edition of Le Figaro, Epi helped private military companies operating in Iraq employ “over a thousand Colombian combat-trained ex-soldiers and policemen.” Some of these men were “trained by the U.S. Navy and the DEA to conduct anti-drug and anti-terrorist operations in the jungles of Colombia” and were “ready to work for $2,500 to 5,000 a month,” said manager Shippy. He promised “considerable savings for a high-quality product” to his clients.

When police looked for the aggressive Shippy, they found his luxury home abandoned. They did discover, however, that he had previously worked for DynCorp, a private U.S. company that illegally sprayed Colombian coca farms.

For its part, Hostile Control Tactics LLC, offered to “provide in-depth training to individuals willing to acquire the necessary skills to do the job.” It promises salaries of “$500.00 per day - up to $1,000.00 per day.” In addition, they offer “bonus pay raises” based on a peer-review system.

Such campaigns to use private mercenaries from Latin America and other parts of the world in lieu of U.S. troops has led to the rise of a parallel army. More than 20,000 non-U.S. mercenaries now supplement the regular troops in Iraq.

A Growing Private Army

On January 17, 2005, El Tiempo reported that Halliburton had “recruited 25 retired Colombian police and army officers to provide security for oil infrastructure in Iraq.” The officers met in Bogota in early December, “with a Colombian colonel working on behalf of Halliburton Latin America, who offered them monthly salaries of $7,000 to provide security for oil workers and facilities in several Iraqi cities.”

Imagine the power such pay holds in a poverty-stricken country! Formerly headed by U.S. vice president Dick Cheney, Halliburton is the recipient of the largest amount of government money for Iraq construction and, along with its subsidiary Kellogg, Brown and Root, has been accused of overcharging and accounting discrepancies. A Colombian government source confirmed the story, El Tiempo reported. Halliburton officials denied it.

Blackwater, another U.S. company that trains mercenaries, sent its pros into a Colombian military school in Bogota with permission from the authorities. Previously Blackwater had recruited and trained Chilean military personnel from the Pinochet days to Iraq. No one knows the exact number of Latin American mercenaries now serving in Iraq. But they may be almost as numerous as U.S. troops.

Hope and Anger

In early October, my friend in the cafeteria asked me: “If they have so many private troops from Latin America in Iraq, why do they need my son?” She smiled sadly. “I hope Carlito - he’s the older one - comes home for Christmas. But he doesn’t know, yet. He’s in a place called Tikrit, now, and says the locals don’t seem to like us all that much. What can I do? I pray.”

Fernando Suarez does more than ask God for help. “Señor Bush,” he shouted to a California student group in the fall of 2004. “Cuantos hijos de nosotros nesecita para lenar su tanque de gasolina? Cuantos hijos americanos muertos nesecita para parar esta guerra llena de mentiras? Yo no quiero mas muertes de nuestros hijos de sus padres, esposos. Paremos esto YA!!! Señor Bush, espero que dios le perdone, porque yo no puedo.” (“Mr. Bush, how many of our children do you need to fill your gas tank? How many dead American children are needed to stop this lie-filled war? I don’t want more our children and wives and husbands dead. Let’s stop this right now. Mr. Bush, I hope God forgives you, because I cannot.”)