KC Adams: Perception, imagery and the fragility of prejudice

Perception. Photo by KC Adams.

“The world in which you were born is just one model of reality. Other cultures are not failed attempts at being you; they are unique manifestations of the human spirit.” -Wade Davis

The publication of a controversial MacLean’s article in January, 2015 sent shockwaves through Winnipeg. Nancy MacDonald’s 6,000-word exposé — “Welcome to Winnipeg: Where Canada’s racism problem is at its worst” — proved a bleak, stirring and uncomfortable read. It was a proverbial wake-up call to a city already numbed by the tragic killing and attempted murder of two young indigenous teenagers only weeks before.

Within hours of its appearance online, the piece was shared thousands of times. It circulated through social media channels, was featured on television news programs and discussed in nearly every social and political sphere. MacDonald had become a messenger of uncomfortable truths; of a reality seldom confronted in the press with such blunt honesty and emotion.

Her work struck a sensitive chord. It forced readers to contextualize their own experiences with racism and observe how harmful attitudes toward First Nations people have led to troubled relationships and pronounced segregation. But could a singular article do anything to lift a community from an apathetic lull, one borne of generations of indifference to the suffering of a settler nation’s most marginalized peoples?

Across all epochs and cultures, art has maintained a strong connection to politics. The former is often a response to the contemporary manifestations of the latter. Art also reflects politics — both are powerful agents of social change — and provides important commentary on modern struggles of humanity, questions of technology and the relationship between the natural and built environment.

For centuries, First Nations people have practiced artistic traditions separate from that of Europe, fusing ancestral folklore, legend and spirituality with various forms constituting an historically unique canon. From pre-colonial works to the better-known Indian Group of Seven (Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporation) and Woodland School founded by Norval Morrisseau and Daphne Odjig, Aboriginal artists have remained at the forefront of Canada’s creative community. Throughout the twentieth century and into the present, they have actively challenged Western or elite notions of ‘legitimate’ art, gained recognition in global circles and acted as vanguards of traditional knowledge and cultural identity.

The thrust of industrial capitalism, however, remains its gravest threat. Canada’s regrettable history of colonization — exacerbated by social engineering within residential schools — has imposed a grotesque racial hierarchy on an otherwise multiethnic and pluralist nation. Today, indigenous people are over-represented in Canadian prisons, poor health indices, disabilities and poverty. They suffer from negative social stigmas perpetuated by problematic relationships with white settler communities, police forces and government officials, and are daily victims of systemic racism.

In Winnipeg, where the urban Aboriginal population is the country’s highest, questions about the state of First Nations identity and its relationship to the Canadian state are discussed passionately. Here, social and economic inequality is stark but transforming, slowly. There is a general understanding, too, that a shift will not occur easily; it will require a collective acknowledgement of the systems that perpetuate poverty and racism, and a demand they change.

KC Adams. Photo supplied by artist.

With her latest project, Perception, KC Adams has made sure the process won’t be a voluntary one.

The Yorkton, Saskatchewan-born First Nations artist has worked for decades as a sculptor, painter and multimedia creator — her pieces have appeared in many solo and group exhibitions throughout North America and Europe — but Perception is the most pointed political statement of her career. It is an effort to challenge deeply engrained social stigma and prejudice, and show the faces of indigenous people, not as disenfranchised and helpless, but dignified and proud human beings.

The concept was influenced by themes in Adams’ earlier work, much of which deals with the destructive relationship between nature and technology in industrial capitalist society. Projects like Birch Bark Ltd. and the Cyborg Hybrids series (featured in the January/February 2007 issue of CD) “challenge stereotypical views towards mixed race categorization, examine the relationship between nature and technology, and explore concepts of identity and community.”

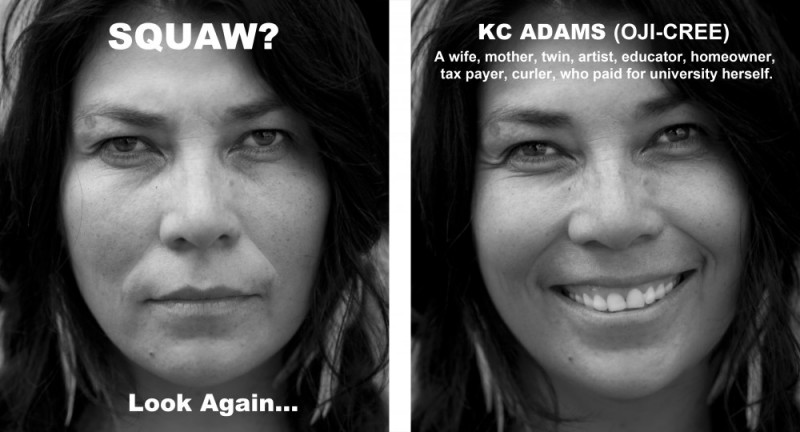

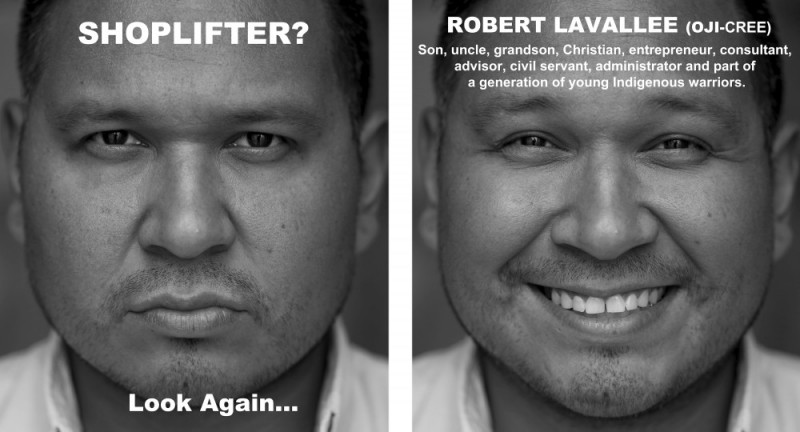

Perception is the result of two years of reflection and concern about the state of indigenous self-identity. Adams sought to expand upon the themes in her previous work, and launched the photographic exhibition in late-March with Urban Shaman Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery in various locations in downtown Winnipeg. The photographic exhibition features a series of two portraits including many prominent members of the city’s indigenous community: the first, on the left, displays a subject captioned with a racial slur; the second, on the right, shows the same face, but titled with the individual’s real name, their occupation, interests and passions.

The politics of representation, so often determined by external forces, the media, reports of crime and poverty, are flipped on their head.

“A couple of years ago”, Adams says, describing the genesis of Perception to CD, “my brother and I were on an all Aboriginal softball team. My sister-in-law, who’s not First Nations, would come to the games. After a while she said to me, Outside of your family, I’ve never been around First Nations people, I had no idea how normal they were. I was taken aback.

“It was this idea that you can’t just label an entire race based on a single stereotype. I really needed to create a piece that showed the individual, to create a dialogue and open the door for discussion. We can’t look at First Nations people from a perspective of us versus them. The discussion has to be about we.”

Perception gives its subjects a chance to define and represent themselves. Each photograph is captured with a short focal length, directing the viewer’s gaze straight into the eyes of the other. To a passerby, it creates a momentary union in public space where the walls of prejudice become invisible. Though it may only produce an ephemeral, transitory experience, it is still an effective one – a moment of clarity where one can reevaluate their preconceived notions based solely on physical appearance.

“I’m getting the models to describe themselves,” Adams continues. “I had a model who was on welfare, for example. That’s not how they define themselves. Jenna, she was a youth at risk. Her backstory is absolutely incredible. Yet, that’s not how she defines herself. She defines herself by what she wrote on her right side. That’s really the point of the work and the conversation. People who feel that I’m just perpetuating the stereotypes aren’t looking at the right side.”

Perception is sure to face criticism as it appears in increasing frequency throughout the city. The same hostility expressed toward to the University of Winnipeg’s recent approval of a mandatory indigenous course requirement will be directed at Adams’ visual art project. The effect resembles what cultural studies professor Robin DiAngelo coined “white fragility” in a 2011 article in the International Journal of Critical Pedagogy:

A state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include outward display of emotions such as anger, fear and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence and leaving the stress-inducing situation.

From even a cursory glance, Perception demonstrates the malleability of attitudes and the fragility of stigma. Its use of photographs, a medium central to our understanding of human faces and identity, serves an emotional and cognitive purpose: it allows one to transcend the shell of appearance and grasp the essence of others.

It will take many generations for the realities of racism to soften, and for the atmosphere described in MacDonald’s article to transform, but Perception affirms the Jungian ideal that all things which irritate us about others, inevitably lead to a more profound understanding of ourselves. Indeed, all of Canada should heed that powerful message.

Perception will appear in downtown Winnipeg until the end of April, 2015. Read more about this visual art project at PerceptionSeries.com, or visit KC Adams’ website here.

Harrison Samphir is an editor, writer and policy analyst based in Toronto. His work has appeared in CBC, Jacobin, NOW Magazine, Huffington Post, rabble.ca, Ricochet, Truthout, and the Winnipeg Free Press, among others. In 2016, he completed an MA in International Relations at the University of Sussex. Harrison has served as Dimension’s web editor since 2014.