Insurgent diaspora against empire

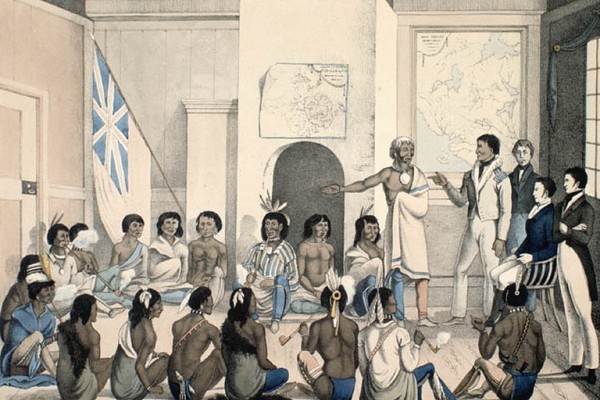

In the waves of anticolonial rebellion throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, opposition from within the centres of colonial power was needed to spark strong movements of resistance and struggle. The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act throughout the British Empire, for instance, was deeply influenced by enthusiastic activism for emancipation based in London. This movement was so distinct, in fact, that Britain went from the biggest slave traders in the world to the most vocal proponents of abolition in just a half-century.

A surface reading of successful independence or emancipatory movements would make it seem, therefore, that European powers voluntarily relinquished their “white men’s burdens.”

While imperial power brokers in European capitals seeking to reduce the reach of their authority may seem benevolent on the part of empire—particularly of the British Empire where independence narratives are associated with decrees from London instead of upheavals in colonial cities—what is typically ignored is the influence that diasporic activists and other influential figures from the colonies had on fomenting anticolonial resistance in these centres.

Key diasporic figures, typically from the petty bourgeois class, organized anticolonial dissent from within the hearts of imperial capitals themselves. Through the global dimension of capitalist empire, members from this bourgeois class would often contrast the excesses of power in European capitals with the abject poverty experienced by their own people, while never fully being accepted within the elite classes residing in the centre.

It is these experiences that radicalized nationalists against their own bourgeois class interests for emancipatory independence controlled by freed slaves, workers and the peasantry. The experiences of famous anticolonial dissidents such as Simon Bolivar in South America and Sun Yat Sen in the Xinhai Rebellion come to mind when examining nationalism, but typical analyses of these episodes of anticolonial dissent frequently exclude how non-white or colonized actors built movements against empires from within.

Priyamvada Gopal’s new book, Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent, offers a thorough analysis of these episodes of rebellion throughout the British Empire from the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny in India, to the Mau Mau Rebellion in 1950s Kenya. Essential to these movements was the interaction of white and racialized activists, bringing forward ideas of freedom from the struggles and constructed poverty of colonial subjects. Emancipatory ideals among British thinkers didn’t just come from their own thought; these ideas were imparted on to them from diasporic anticolonial resistance.

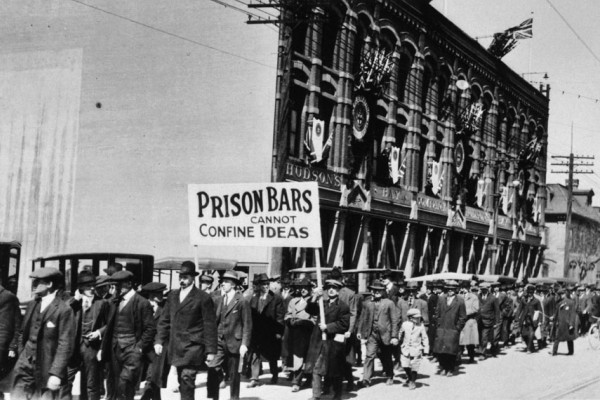

One of the key figures Gopal examines is Shapurji Saklavata, a Bombay-born British Labour (and later, Communist) MP for North Battersea. As an elected representative in the 1920s, Saklavata spoke with authority in defence of the British working class, simultaneously tying its struggle under capitalism to the anticolonial struggles under the Indian Raj. Though anticolonial voices were typically subdued in the colonies through strictly enforced anti-sedition laws, inalienable rights to the freedom of speech that came with the turn of liberal capitalism ironically allowed dissenting voices to gain traction in London. Saklavata was thus able to dissent against the British Empire from within Westminster, influencing activist discourse and movements from the very centre of colonial power.

Insurgent Empire provides a rare opportunity for non-white voices of dissent from the heart of empire such as George William Gordon and CLR James to be heard within the total narrative of rebellion against the British Empire. Resistance was also not heterogenous, either in ideology, violence, or other contexts which affected outcomes and the duration or intensity of rebellious episodes.

Gopal’s strong academic analysis of primary source material may warrant a less casual reading of this work, but it is no less important in dismantling common myths of the benevolence of the British Empire. The book also provides insight into how communities were imagined by revolutionaries: not simply as vassal capitalist states in a redefined neocolonial order, but as republics that provided democratic control to workers and the peasantry. Together, these insurgent episodes and constant struggles across the British Empire should define the history of its demise, rather than decrees from Westminster.

Clement Nocos is an Ottawa-based policy analyst and writer.