Hollowing-Out

To live under external ownership and control has been the common fate of Canadians, and has powerfully conditioned our lives and our politics. Aboriginal people were so treated from early on by the settlers who, in turn, embraced their own lot as imperial subjects. As formal sovereignty shifted over time to the margin of empire, the tendency nevertheless was to welcome foreign capital to Canada, even to proclaim loudly that Canada was “open for business.” The rising American corporation of the late nineteenth century spilled over the border into Canada to the applause of Canadians.

It was not until the second half of the last century that Canadians had a sufficient sense of themselves as a people to articulate a concern about what was, by global standards, an extraordinarily high level of foreign ownership and control. By then, the Canadian business class was so deeply embedded in imperial (now American) structures that it stood overwhelmingly against any assertion of Canadian nationalism. Under the Trudeau Liberals, there was a willingness to make concessions to Canadian nationalism, the better to put down Quebec nationalism. A Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA) was created to oversee foreign takeovers, a Canada Development Corporation to assist in the funding of Canadian enterprise and state-owned Petro-Canada for a sector dominated by foreign-based giants.

All of this was to be swept aside in the face of a new round of neoliberal, pro-market restructuring and consolidation of capital that passed under the name of globalization. The Canada Development Corporation and Petro-Canada were privatized. FIRA was renamed Investment Canada, and was explicitly assigned the task of getting more foreign investment. Since its creation, it has approved every application for foreign investment that has come before it; it is nothing more than a giant rubber stamp that can function without human intervention.

It is reasonable to insist that the operations of Investment Canada, which are now conducted in secret, be made transparent – that when acquiring companies make commitments, as Investment Canada says they do, we are told what these are, and that there is machinery in place to monitor the keeping of those commitments.

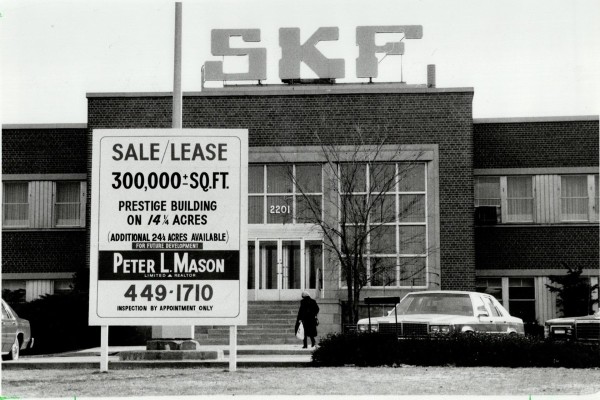

By the first decade of the new millennium, the burgeoning wave of mergers and acquisitions had gobbled up such Canadian icons as Inco, Alcan, the entire steel industry, perhaps even BCE if you can figure out who actually controls it de facto. Once upon a time, Canadians had worried about being reduced to a branch-plant economy. Now we worry that the flight of head offices is leading to a “hollowing out” of corporate Canada and the Canadian economy. The best scholarship – that of legal expert Harry Arthurs – suggests that this is happening, that the issue is not simply jobs in head offices (as StatsCan pretends) but also jobs in business services, like legal and accounting services and consulting and advertising agencies.

In Lock-Step with the U.S. Economy

Canada has long been a resource-based economy with staple exports leading the growth process. Today the world is in the midst of a great commodities boom, with prices spiraling upward. Resource companies are piling up huge surpluses, which they can use to take over other companies. Indeed, if they fail to do so, they become the targets for takeover by those who do play that game. Canadian resource companies like Inco, Falconbridge and Alcan have fallen into the hands of foreign giants.

What the federal government is concerned about is whether foreign, state-owned enterprises should be allowed to take over Canadian companies. This appears to be code for not letting Chinese companies invest in Canadian resources – the major benefactor from such a policy presumably being American companies. It also wants Investment Canada, in considering “net benefit” of foreign investment for Canadians (which is what it is mandated to do), to weigh any adverse consequences for national security. This is a delayed effect of 9/11, linked with the “War on Terror.” There is a very real risk that Canadian policy in this area will lock us even more tightly into the policies and practices of the American homeland-security state. It is unlikely, to say the least, that “national security” will be defined as security of energy supply for Canadians, though it would make a lot of sense to do so.

Beyond that, the government mouths the standard line that the business environment needs to be made more corporate-friendly so that Canada will be a base for outward investment. At the top of the wish list is cutting corporate taxes, though it is hard to think of anything stupider than giving more tax breaks to resource companies making super-profits.

Fighting inward foreign investment through more outward foreign investment has the deep flaw that, when Canadian companies go abroad, as in mining, they violate human rights and degrade the environment the same way other countries’ corporations do. If there are distinctive Canadian values, they are not evident here.

Takeover After Takeover

Where restrictions on foreign ownership have a history in this country – and have worked – is at the sector level, in banking and finance and in communications and culture. There is much talk in the business press about lifting these restrictions – in effect permitting Canadian firms in these sectors to merge at home so they can be big enough to play the global game of consolidation.

That is likely to be the terrain on which foreign ownership will be debated in the foreseeable future. Competition at home (such as it is) will be sacrificed in the name of competition abroad; benefits to Canadians as consumers are unlikely. Those of us not enamoured of the virtues of foreign ownership will be fighting a rearguard action to maintain the restrictions we have in telecommunications and banking, though it would make sense for us to push for extension of such a regulatory regime into oil and gas, with emphasis on public ownership as the alternative to foreign ownership.

Toward a New Economic Nationalism

The Left should resist any tendency on nationalist grounds to support the creation of national champions. Besides the problem of how they behave abroad, there is the fundamental issue of the role of mega-corporations regardless of country of ownership. They are part of a package of more international investment and more international trade and more transportation of goods and more business travel – and that is the package that delivers more global warming without end. The time has come to talk about de-linking from the global economy, of lessening the links – not enhancing them – of opposing mergers, acquisitions and takeovers. The Left will not find corporate allies in that struggle.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Left in the main supported economic nationalism. In recent decades, it has opposed corporate globalization. We need to redefine the former while maintaining our focus on the latter. In short, we need to articulate new alternatives at both the national and global levels for the sake of future generations, since such alternatives may be necessary for human survival itself.

This article appeared in the January/February 2008 issue of Canadian Dimension (Big Media).