Does ‘anti-racism’ contribute to racism?

Photo by Ted Eytan

Let us begin with a heretical proposition: anti-racism may contribute not to combatting racism but to actually deepening it. How could this be possible? One of the key elements of anti-racism is the politics of representation, which is meant to challenge not only the structures of white supremacy but also other systems of domination such as patriarchy. The clearest example of the politics of representation was that of the election of Barack Obama as 44th President of the United States in November 2007. More recently, in Canada we have the more recent example of the first Sikh leader of a federal political party, namely Jagmeet Singh, who last fall was elected leader of the New Democratic Party. The politics of representation or recognition are by no means inconsequential. It is surely not insignificant that African-American children can today imagine themselves occupying the highest office in the land, nor that, with the ascension of Jagmeet Singh, South Asian children can imagine themselves as genuine contenders to be Prime Minister of Canada.

However, thinking that somehow by simply by having an African-American President or possibly an Indo-Canadian Prime Minister — what Keeanga- Yahmatta Taylors calls “Black faces in high places” — will, in itself, address racism, is profoundly naive. That Obama’s presidency was materially damaging for most African-Americans is clear. As Taylor points out in From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, “Since Obama came into office, black median income has fallen by 10.9 per cent to $33,500, compared to a 3.6-per-cent drop for whites, leaving their median income at $58,000.” Indeed, the conditions of socioeconomic inequality only deepened with a president who, in the midst of the financial crisis of 2007-08, bailed out the banks while ordinary Americans — black and white alike — lost their homes. This, in part, laid the groundwork for the election of Donald J. Trump.

In the past, the politics of representation in the labour movement and in political parties was regarded as a key strategy to redress power asymmetries based on race and gender. For example, when I was a student in the mid-1980s at the London School of Economics, there was a heated debate within the Labour Party over the creation of “Black Sections” amidst the then (as now) pervasive racism of British society, racial profiling enabled by the socalled “Suss Laws” and the collective anger of black British communities that expressed itself in the Brixton and Toxteth riots in the late summer of 1985. Black and women’s caucuses are important forms of representation, whereby structurally disenfranchised groups can properly advocate for policies that address the unique experiences of oppression that cannot be properly subsumed under larger more general categories such as “the working class.” “Separateness” here functioned as the means for transformation of structures of power in the struggle for a more justice and equitable society over all. It was never intended as an end in itself.

Fetishizing language

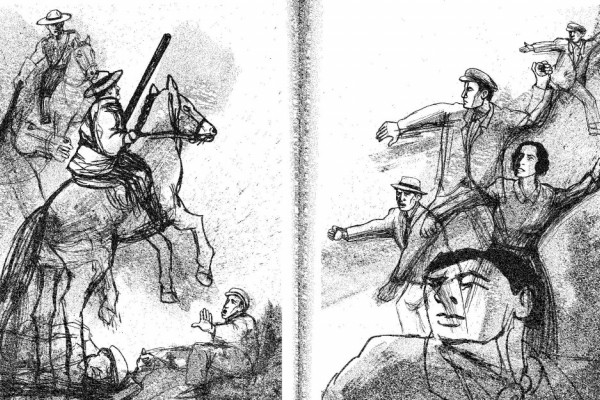

Today, in contrast, it seems that this politics of representation has become an end in itself. With this has come an inordinate emphasis on a fetishization of language as a way to address racism. This stems from the important and valuable insight that language does play a key role in racial domination. For example, it played a key role in both European colonization of Asia and Africa and the Holocaust which it, in part, inspired, a prelude to genocide as the dehumanization of the “other.” The colonized were referred to “barbaric” or “savages,” the Jews were regarded as “cockroaches or as rodents.” In both cases, the dehumanization of the other via language was a necessary prelude to total domination and, in the case of European Jews, of course, genocide.

While it is therefore no doubt important to focus on language, this emphasis has often come at the exclusion of the material sources of the very rationale for colonial domination in the first place: capital accumulation. Today, much anti-racism takes the form of policing speech and expression and, increasingly, the advocacy of “safe spaces” in which persons who “identify” as members of a given oppressed group can address issues of common concern relatively free from the so-called “micro-aggressions” of dominant groups. Solidarity has come to be replaced by “allyship.” What escapes from view, as I shall suggest below, is an real analysis of the way in which racism stems largely, though perhaps not exclusively, from socioeconomic inequality and social insecurity.

Until these sources of racism are addressed, all that will remain is a moralistic policing of its inevitable expressions. Eventually, individuals and groups will feel increasingly emboldened to transgress these norms of comportment. And, because the antiracist Left has targeted “Whiteness” (often in ways that make it inextricable from white people as such) it has from the outset disqualified itself from building cross-racial class-based alliances — the only kinds of alliances, in my view, that possess sufficient power to actually challenge, win concessions from and transform capital and therefore the structure of racism which is based upon it.

This emphasis on “whiteness” or “White Supremacy” becomes its own circular explanation when detached from socioeconomic inequality and relations of exploitation. It was the means by which divisions were created and maintained among workers in the interest of maintaining their continued domination. Detached from the material conditions of production and distribution that give rise to it — so clearly evidenced by writers such as Ta-Nehisi Coates — is especially dangerous and, again, can have the effect not of ameliorating but deepening racism.

How? Because, even if it is not intended to, attacks on “whiteness” can be experienced by white people as personal attacks on themselves. Not only will it make it less likely to engage in a counterhegemonic politics whereby multiple groups with different though potentially over-lapping demands can coalesce into mass opposition to the dominant “power bloc,” it could actually drive those workingclass whites into the clutches of the far right. The identity politics of the Left can actually be seen not as counter but as provoking an already latent white “identitarianism,” to use neo-Nazi Richard Spenser’s term. As Hannah Arendt once put it, if you are attacked as a Jew, you fight back as a Jew.” By virtue of the same logic, “If you are attacked as a white, you fight back as a white.” And this logic cannot but be disastrous.

Liberal identity politics

In Canada, we have seen over the past two years such a politics of representation at work in the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau, a self-described “feminist” who declared boldly, shortly after his party’s election, that his cabinet was to be fifty per cent female “because it’s 2015.” Trudeau also appointed an Indigenous person, Jody Wilson-Raybould, to the important position of attorney general/ minister of justice — a previously out-spoken advocate for Indigenous Treaty Rights and for the implementation of UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). However, Trudeau has no compunction about dealing arms — for use in a brutal war against the Houthi rebels in Yemen — to Saudi Arabia, a state that is not exactly known for the equitable treatment of women by any standard. It is, moreover, not particularly clear how his government is improving the material conditions of the majority of women, particularly the most disenfranchised among them, working-class women of colour and the indigenous women and girls who have historically been victims of structural violence. And the Liberal government has not hesitated to go back on its promise to implement UNDRIP nor to approve of the twinning of a Kinder Morgan pipeline in the greater Vancouver area against the express wishes of local Indigenous communities fearing that an oil spill would irreversibly alter their traditional fishing waters. Wilson-Raybould’s silence on the issue today, after her previous advocacy, itself speaks volumes about the government’s politics of representation. In other words, the politics of representation are mostly symbolic.

It is against this backdrop that, last October, the New Democratic Party had its leadership convention and chose, in a historic vote, the dashing Sikh lawyer Jagmeet Singh by a massive margin over a strong pool of candidates. The pool included a young, brilliant, multilingual female MP, Niki Ashton, who sought explicitly to take the party to the left, although this is perhaps better described as bringing the party from the radical centre back to its social-democratic roots. Ashton sought to integrate some of the lessons learned from the Sanders campaign, and also from the remarkable success of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. Ashton sought not just the leadership but to build a movement around social, economic and environmental justice and sought inclusion of Indigenous peoples and LGBTQ+ groups.

Ashton was blasted for engaging in “cultural appropriation” for having the temerity to use Beyoncé’s apparently apt song “To the Left” in her campaign. She immediately dropped the song in response to a single tweet from #BLM Vancouver and apologized. This was itself probably an ill-judged decision insofar as it could have been an opportunity to initiate a discussion on whether such a profoundly marketed and commodifi ed artist could be culturally appropriated. Not only that, the implications of the tweet are that white leftists would never be able to use music by any black artists such as Paul Robeson, Curtis Mayfi eld, LKJ, Bob Marley — all artists whose work had a profound political resonance. More troublingly, it seems to suggest that white people must stick to “white music,” whatever that means.

An appeal to justice

Jagmeet Singh won the day on the basis of campaign situated in the “radical centre” built around a nebulous appeal to “courage” and “love.” However, troublingly, one of the key planks of his leadership nomination platform was not so warm. This was to open up a discussion of the universality of a vitally important social program in this country, the Canada Pension Plan. That is, he fl oated the idea of means testing an entitlement that people actually pay into from deductions on their pay packet. This has led to worries that if the NDP were ever to win power it would not break with but perhaps deepen the hold of the neoliberal status quo by further weakening what little remains of the Canadian welfare state.

Jagmeet Singh,

June 25, 2017,

at Pride Parade;

Wikimedia Commons

A key question that needs to be asked is as follows: Could Jagmeet Singh be regarded as just another “brown face in a high place”? His election as party leader was indeed historic, though clearly not on the order of Obama’s 2008 election, and this must at some level be seen as a victory for a kind of anti-racism. And this brings me to the question I posed at the outset: Could such an anti-racism, despite its best intentions, contribute to racism?

I think the answer must be yes. Racism, as I’ve already suggested, is not to be explained by terms such as “White Supremacy” — for this would be a tautology — but by virtue of its deep connection to socioeconomic inequality. As the great Martiniquean revolutionary and psychiatrist, Frantz Fanon, argued “What matters today… is the need for a redistribution of wealth. Humanity will have to address this question, no matter how devastating the consequences.” If this is the case, then the best anti-racists may, in fact, be white people, such as Niki Ashton, Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, with credible plans to ameliorate socioeconomic inequality rather than those black and brown people like Barack Obama and Jagmeet Singh who become the acceptable faces of neoliberal inequality. “Some blacks,” Fanon argued, “can be whiter than whites” and that some “colonists” “can change sides, go ‘native,’ and volunteer to undergo suffering, torture and death.”

Samir Gandesha is Associate Professor of Humanities and the director of the Institute for the Humanities at SFU. He is co-editor with Johan Hartle of Aesthetic Marx (Bloomsbury, 2017) and Spell of Capital (Amsterdam, 2017).

This article appeared in the Spring 2018 issue of Canadian Dimension (Whiteness & Racism).