Deconstructing Loblaw’s inept self-justification

Canadians are having a visceral reaction to the smug corporate power projected by the major supermarket chains

Loblaw’s inept efforts on social media to justify its super-sized inflation-fueling profits provide an opportune moment to remind shoppers of the crucial economic facts regarding supermarket profitability. Photo from Flickr.

Of all aspects of the recent surge in inflation, the one that certainly generates the most anger among Canadians is the rise in food prices. This is totally understandable.

Food is an essential commodity: we all must eat. We go to the store every week, and are confronted face-to-face with the painful reality of surging food prices. The average price of groceries increased 11 percent in the last year, much faster than even the overall inflation rate (which averaged 6.3 percent over the same period).

Canadians also have a visceral reaction to the smug corporate power projected by the major supermarket chains. The three biggest chains (Loblaw, Metro, and Sobeys) control, including with their numerous subsidiary brands (Food Basics, Superstore, etc.), almost two-thirds of food retailing in Canada. Loblaw’s advertising, featuring Galen Weston (one of Canada’s richest people) artificially dressed down in a cardigan, is particularly patronizing.

Past exposés of anti-competitive behaviour by supermarkets—like the long-running scandal over price-fixing for bread products, or the simultaneous decision by all three chains to cut wages for grocery clerks by $2 per hour after the COVID lockdowns—have made Canadians rightly suspicious of the greed and power of these companies.

It’s not surprising, then, that supermarkets have become a target for public anger over the cost of living crisis. Politicians of all stripes, sensing this anger, have vented as well: calling supermarket executives before a special House of Commons committee hearing (initiated by NDP agriculture critic Alistair MacGregor). The Competition Bureau has also launched an investigation into supermarket prices.

These efforts, despite their sound motivations, are not likely to amount to much. The nature of the Parliamentary hearing did not allow a deep dive into the economic data of supermarket profits. The politicians made speeches, and the executives easily rebuffed most of the complaints. The Competition Bureau’s investigation will be constrained by the weak nature of competition law in Canada, which has limited scope to change corporate behaviour or levy meaningful punishments. Nevertheless, public anger continues to bubble.

The supermarkets complain they are being unfairly singled out for responsibility for food inflation. They claim they are innocent victims, caught in the middle: merely passing along higher prices they are charged by their own suppliers. They invoke far-fetched mathematical arguments and jargon (including vague references to ‘profit margins’ and other financial ratios) to pretend their profits are not unusual—even though they are at record highs (confirmed by their own financial reports). These arguments have not washed well with the shopping public, every time they shell out $200 for a cart of groceries.

Loblaw’s PR flacks even jumped head-first into social media on January 31, with a special offensive to deflect criticism over its prices and profits. That was the day a much-trumpeted ‘price freeze’ on Loblaw’s cut-rate No Name product line (announced with fanfare by Galen Weston last October) expired. The price freeze itself was not a meaningful action: retail experts pointed out that prices are regularly frozen over a ‘blackout’ period covering the holiday season—but the gimmick generated lots of free publicity for Loblaw.

With the price freeze coming off, Loblaw rolled out an army of spin-doctors to challenge (in both the commercial media and online forums) any complaints about renewed price increases. Posters on Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit were surprised to receive personalized responses to their complaints from the company’s PR team, invoking the usual jargon about Loblaw’s innocence.

This strategy was not successful, likely generating even more anger among most consumers. Why not reduce PR expenses and fractionally reduce the cost of groceries instead?

Loblaw’s inept efforts on social media to justify its super-sized inflation-fueling profits provide an opportune moment to remind shoppers of the crucial economic facts regarding supermarket profitability.

Below I have outlined four key indicators showing that Loblaw and the other chains are not innocent intermediaries. They have seized the opportunity provided by the volatile conjuncture of disrupted supply chains (from the pandemic, climate disasters, and the war in Ukraine) and consumer desperation, to jack up prices far beyond what would be required to cover their own input costs.

Food retail profits have doubled compared to pre-pandemic norms. Statistics Canada data shows food retailers have earned about $5 billion per year in net income since COVID, more than twice what they earned in 2019.

Those higher profits are not the result of a constant profit margin collected from a growing base of sales. The supermarkets and their flunkies claim ad nauseum that supermarket profits are up only because total sales have increased; their ‘profit margin’ (defined as the ratio of some measure of profit to total revenues) has been stable, they claim. These arguments are outright lies. The average net profit margin in food retailing has increased by about three-quarters since before the pandemic, and has remained elevated even as the economy re-opened and inflation took off.

Perversely, the quantity of food sales has been falling since the lockdowns. Supermarket sales spiked during the initial lockdowns as a result of panic buying and the closure of restaurants. Sales remained unusually high for the rest of 2020 and early 2021. Then, as inflation took off, the real quantity of grocery sales began to decline—and it is now lower than volumes sold before COVID (despite three years of population growth since then). Painfully, Canadians are actually buying fewer groceries than before the pandemic—but paying much more for them. This attests to the hardship and even hunger that many Canadians are experiencing as a result of this crisis. And far from collecting a constant profit margin from a growing business, supermarkets’ real business is actually shrinking. Yet their profits are up strongly, anyway.

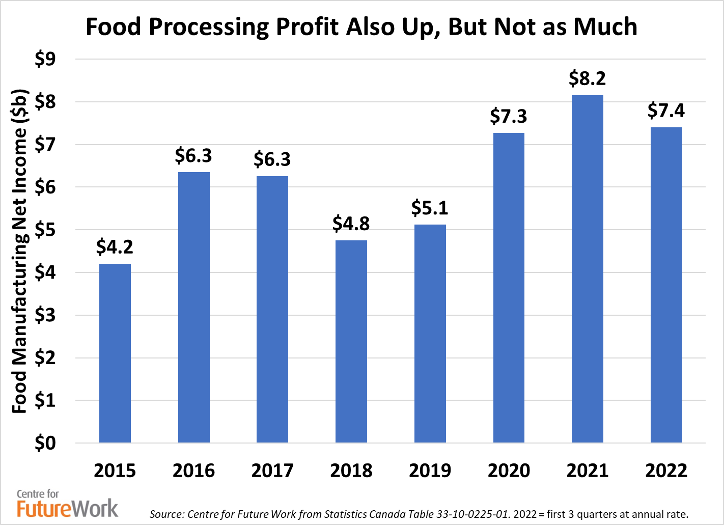

Yes, food processors are also jacking up prices and earning higher profits. Supermarkets are indeed paying more for the products they buy from their own suppliers, which they then resell to final customers. Supermarkets have increased their prices above and beyond what would be required to cover those higher supplier costs (thus explaining their rising profits and profit margins). But like the supermarkets, food processors have also increased prices more than justified by their own increased costs (for raw materials, agricultural output, labour, energy and transportation). Food manufacturing profits have also grown since the pandemic: up 42 percent in the latest 12-month period, compared to 2019. That’s less dramatic than the doubling of profits in food retail, but food processors’ greed has nevertheless contributed to excess inflation in the overall food supply chain.

We don’t have to take sides in finger-pointing between oligopolistic food retailers like Loblaw, and oligopolistic food processors like Cargill or PepsiCo. They blame each other, trying to evade criticism over their own profits. But both of these powerful corporate blocs have taken advantage of supply disruptions and consumer desperation to fatten their profits, amidst the deep economic and social crisis gripping our society. Indeed, both food retailers and food processors rank among the key sectors in Canada’s economy that have caused most of the inflation experienced by Canadians—and not coincidentally captured the biggest increases in profits, as a result. In recent research published by the Centre for Future Work, 15 super-profitable sectors were identified as the main causes of higher Canadian inflation.

These 15 sectors account for all of the economy-wide growth in corporate profits since 2019. After-tax corporate profits reached a record share of Canadian GDP during the post-pandemic surge in inflation; these strategic sectors have captured all of that surplus (aggregate profits in the rest of the economy declined in the same period). It won’t be a surprise to Canadians that the industries that raised prices the most, have also experienced the biggest growth in profits.

However, the supermarkets and food processors are in good company. As shown in the table, there are 13 other sectors which have profited even more dramatically from the pandemic and resulting disruptions. Leading culprits include the petroleum industry (whose profits rose over 1,000 percent), banking, mining, real estate, building materials, and new car sales.

The fact that supermarket super-profits are not unique (and actually slightly less outrageous than those in other strategic sectors) does not let Galen Weston and the other food barons off the hook. The evidence is clear: supermarkets have taken advantage of the pandemic and its aftereffects to extract more surplus from their workers and consumers. That greed has contributed to inflation, and should be challenged: with excess profit taxes, stronger competition rules, and better labour standards.

But our fury at the supermarkets should be the start of a bigger conversation about the power of corporations to charge whatever the market will bear, even in a social and economic emergency. The enormous profits captured by oil and gas companies, banks, real estate speculators, and other strategically positioned businesses are undermining the standard of living of most Canadians, causing inflation, and now sparking a myopic counter-reaction by the Bank of Canada that is likely to end in recession. That’s the last thing Canadian workers need after the chaos of the last three years. But the line of accountability for that recession goes past the Bank of Canada and its aggressive interest rate hikes, to the corporations whose greed and opportunism sparked the inflation in the first place.

In short, the anger being rightly vented by Canadians at supermarkets every time they go shopping, should burn brightly every time we are ripped off by an economy that is organized to maximize private profit, rather than meet human needs.

Jim Stanford is the director of the Centre for Future Work. He divides his time between Vancouver and Sydney, Australia.