Canada’s duty to consult: a legal veneer for colonialism?

The Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate is all too often a tool for extractive capital

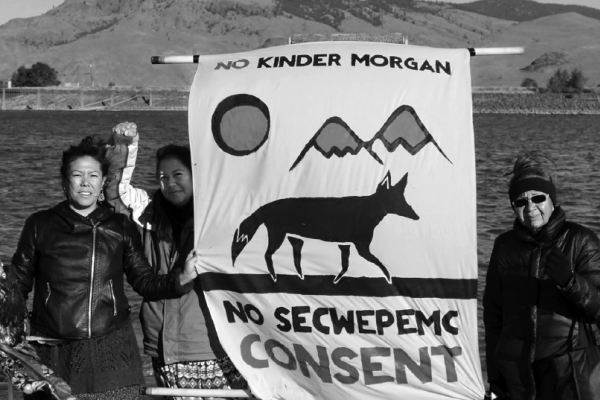

The duty to consult has been at the heart of a number of important legal cases in Canada, but it is skewed toward colonialist justifications for capitalist extraction instead of Indigenous self-determination. Photo by Joel Angel Juarez/Zuma Press/PA Images.

More than 15 years after the duty to consult and accommodate (DCA) was first contemplated by the Supreme Court of Canada in Haida Nation v. British Columbia and Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia, situations still abound where both the adequacy of consultation, and consultation’s efficacy in promoting justice for Indigenous Peoples, are questionable.

Whether it’s ongoing opposition to the Site C dam in British Columbia, controversy surrounding lobster fisheries in Nova Scotia, or invasive mineral exploration in the Yukon, application of the DCA has repeatedly failed to secure definitive legal wins.

The DCA is one avenue by which Indigenous peoples may pursue justice within the Canadian legal system, but it is not at all clear whether it is particularly useful or conducive to the results and conversations Indigenous Peoples might hope for. This is because interpretation and implementation of the DCA has skewed toward colonialist justifications for capitalist extraction instead of deliberation or Indigenous self-determination.

For the uninitiated, the duty to consult and accommodate is a legal duty of the Canadian government that, as the phrase suggests, requires the Crown to consult and potentially accommodate Indigenous peoples whenever, as the SCC states, “the Crown has knowledge, real or constructive, of the potential existence of the Aboriginal right or title and contemplates conduct that might adversely affect it.”

The Crown polices itself

This duty originates in what courts have termed the “Honour of the Crown,” a legal concept that may been traced back to the early period of European colonization and derives from the Canadian government’s responsibility to reconcile “pre-existing Aboriginal societies with the assertion of Crown sovereignty.”

Obviously, the assumption of Crown sovereignty and its legitimacy is a problematic aspect of this doctrine, but we should also be aware that the Honour of the Crown (and resultantly the DCA) is a limitation that the Canadian crown places upon, and interprets, itself. This leaves the door open to interpretations that perpetuate colonialist relations of domination and ultimately serve as legal justifications for extractive capital, rather than legitimate and consistent rules that empower Indigenous sovereignty.

This type of interpretation can be seen in many recent DCA decisions, but is perhaps most obvious in Tsleil-Waututh Nation v. Attorney General of Canada. On an initial accounting, this case might seem like a straightforward win for the applicants. The Federal Court of Appeal found that the National Energy Board (since renamed the Canadian Energy Regulator) had not properly scoped its assessment of the impact that the Trans Mountain pipeline—and the predictable increase in tanker traffic—would have on the Southern Reach orca population, and had thus failed to discharge the Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate.

However, what is most striking about this decision is that while the applicant First Nations raised many instances in which the consultation process chosen by the Crown was itself inadequate, the court wholly dismissed these concerns and focused on the degree to which the Crown had not fulfilled the process that it had selected for itself.

This raises the issue of lopsided adjudication mentioned earlier. While the court went out of its way to provide an analysis of why Canada’s chosen consultation process was reasonable and sufficient to discharge the DCA, it showed little to no deference to the assessment of those best placed to make such an evaluation and on whose behalf the consultation was ostensibly taking place: the impacted Indigenous peoples.

The case is one example of how the DCA can be reduced to a mere responsibility on the part of the government to do as it says it will, rather than a substantive responsibility to engage significantly with Indigenous peoples on matters of process and outcome. In this way, the DCA may serve as a justificatory cover for predetermined decisions and actions, rather than a significant opportunity for Indigenous peoples to negotiate, and potentially force, changes to decisions and actions. Used in this way, the DCA is little more than a legal veneer for continuing colonial domination via capitalist extraction.

Indeed, such regressive interpretations of the DCA on the part of the courts may be understood as attempts to justify colonial undertakings using means provided by the Canadian legal system. This argument is articulated powerfully in Gordon Christie’s 2005 article “A Colonial Reading of Recent Jurisprudence: Sparrow, Delgamuukw, and Haida Nation.” Christie makes the case that “contemporary jurisprudence not only borrows from colonial justifications developed and maintained during Canada’s overtly colonial period, but actually sanctions, affirms and strengthens this colonial conceptual framework.”

Trans Mountain pipeline protest. Photo by Mark Klotz/Flickr.

Blunting Indigenous opposition

This can happen in two ways: contemporary interpretations of the DCA privilege Crown conduct and vision over Indigenous law and vision (rather than attempting to reconcile the two), and funnel Indigenous opposition toward the predefined bounds of Canadian law as the only “legitimate” option. In Tsleil-Waututh, the court defaulted to a view of the relations of capitalist extraction as natural (so long as they conform to the minimal procedural rules they set for themselves) and reinforced the idea that Indigenous legal orders and resistance must be channelled through the Canadian legal apparatus to be considered “legitimate.”

This assimilative pressure effectively links the DCA to Canada’s colonial history by reinscribing an attitude wherein the law’s primary purpose is, as Christie explains, “justifying the taking of Aboriginal lands and the arrogation of jurisdictional authority from Aboriginal nations.” In its current form, the DCA was never meant to empower Indigenous peoples or even to promote deliberation, but to further embed Indigenous peoples within the strictures of Canadian colonial law. In this understanding, it is very much part of a “kinder and gentler taking of land.”

All of this redounds to the benefit of extractive capitalists. Indigenous land and rights claims are an increasingly large thorn in the side of corporations that specialize in the harvesting of natural resources, but court decisions that effectively blunt the sharp tip of Indigenous opposition limit the potential for legal resistance to ever create transformative change.

As in most areas of Canadian law, courts are more interested in legitimating and maintaining capitalist relations of domination than in providing real justice. Opposition to extraction should focus on transforming or working outside of the current legal system, since the DCA as it is used today is woefully inadequate, and sometimes even actively detrimental, to the attainment of justice for Indigenous peoples.

Peter Hillson is a law student at Osgoode Hall and a candidate in the master’s program in Environmental Studies at York University. His research interests include Indigenous sovereignty, climate justice, and environmental law.