Addiction among the middle class

In recent years, my newsfeed has played host to a steady trickle of articles documenting the alarming rise of opioid addiction rates in North America. Described by political pundits as a “quiet epidemic,” the explosion in the use and abuse of pharmaceutical opioids—substances with clinical names like oxycodone, fentanyl, hydromorphone—has gone largely unnoticed, media coverage often limited to celebrity overdoses and litanies of dreary statistics. To be sure, the numbers are staggering; fuelled by a complex web of factors—not least the lobbying efforts of big pharma—rates of addiction to prescription opioids have increased dramatically in the last decade. As of 2014, more than 2.4 million Americans were addicted to doctor prescribed opioids, with overdose deaths reaching an all-time high in that country. In Canada, the world’s second largest per-capita consumer of opioids, prescription figures have skyrocketed and an estimated 200,000 people now count themselves among the addicted.

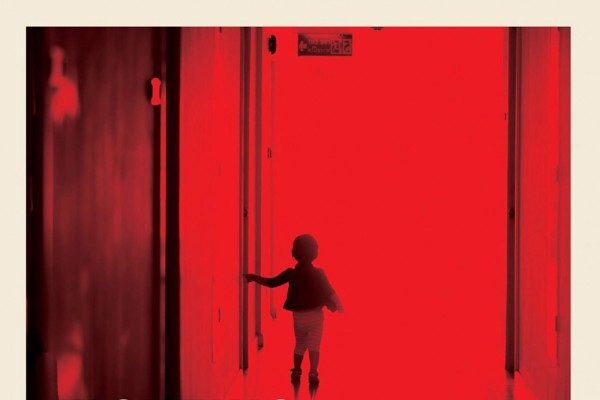

But numbers only tell you so much, and as an inveterate drug nerd, I’ve found myself wondering about this emerging army of addicts; who are they, and what shape do their lives take? Opioid addiction, once the domain of the romantic poets, has for the last 70-odd years been dominated by the figure of the junky, a gaunt, track-marked member of the urban underclass, caught in the perennial search for the next fix. And yet if this old drama of addiction played out against the sordid backdrop of the flophouse, the ghetto corner, and the back alley, the new one seems to be characterized by more familiar scenes: the pharmacy pick-up counter, the doctor’s office, the suburban home.

Carolyn Zwarenstein’s Opium Eater: The New Confessions provides a fascinating tour of this emerging landscape of addiction. Equal parts diary, history, and sociological analysis, Zwarenstein’s book-length essay weaves together personal reflection with science, literature, and posts from online addiction-support forums to produce a compelling picture of modern opioid addiction. The final product, whose title plays on Thomas De Quincey’s celebrated 1821 memoir Confessions of an English Opium Eater, offers an even-handed look at the perils and, yes, pleasures of opioid addiction while offering no easy answers.

Zwarenstein herself is no stranger to opioids. A freelance journalist and mother of two young children, she’s first prescribed the opioid painkiller tramadol for AS, an inflammatory spinal condition that makes carrying out even simple tasks excruciating. Though relatively weak compared to its famous cousins heroin and oxycodone, Zwarenstein quickly finds herself falling under tramadol’s spell, seduced by the drug’s ability to induce a state of calm, detached euphoria. With opioids, the crippling pain and depression associated with AS melt away, allowing her to focus on—and even enjoy—writing, childcare and other formerly unbareable quotidian tasks.

Increasingly dependent on tramadol to carry her through her daily routine, Zwarenstein soon finds herself slipping gently into addiction, taking higher and more frequent doses as she seeks to relive the ecstasy of her early experiences with the drug. Her appetite for tramadol is mirrored in a new fascination with the opioid experience, which sees her scouring the literature in an attempt to unravel the mysteries of the poppy and its derivatives. She finds a kindred spirit in the 19th-century romantic essayist De Quincey, whose writings on his own decades-long opium habit serve as the stimulus for many of Zwarenstein’s musings on the nature of addiction and the seductive appeal of the opioid experience.

These musings are fleshed out with references to a fascinating range of sources; Zwarenstein is an eclectic reader, and the latest addiction science is skillfully set against the work of romantic poets and cultural theorists. On internet forums, she encounters an online community of functional addicts who use opioids to manage the emotional and economic stresses of their middle-class lives; some of the book’s most poignant moments come from these anonymous addicts, whose tales of using at gyms, jobs, and birthday parties capture the surprisingly mundane nature of modern opioid addiction. Self-aware and inquisitive, Zwarenztein’s eloquent reflections on her own addiction give her writing a needed solidity.

While she is obviously dismayed by her slide into addiction, Zwarenstein makes no secret of the fact that the opioid experience is extremely enjoyable—significant swaths of the book document the pleasurable sensations and enhanced creativity opioid drugs engender. As a long-term pain patient, she is also sympathetic to the need for relief these drugs seem to meet; where others see only the sinister machinations of Big Pharma driving rising prescription rates, Zwarenstein points to a new medical paradigm more willing to acknowledge the life-derailing challenges of chronic pain. At the same time, she recognizes the “dead end” of addiction and points a critical finger at doctors and drug companies who seem only too happy to dole out pharmaceutical opioids without much patient oversight. In the end, Opium Eater offers no easy answers, leaving readers to decide for themselves the place for these powerful substances in our world.

Joshua Eisen wears a lot of hats (anthropologist, filmmaker, journalist, angst-ridden member of the precariat) and lives in Toronto.

This article appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Dimension (Fight for $15).