A post-pandemic social peace accord?

The question of who pays for the crisis will not be settled by enlightened policies from on high but through the class struggle

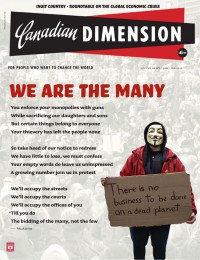

There is no golden age of reciprocity ahead, writes John Clarke. The capitalist system is in crisis and a capacity to rebound and broker peace deals is lacking. Still image from YouTube/The Guardian.

Last week’s federal budget was an exceptional opportunity for the Trudeau Liberals to polish up their ill-deserved progressive credentials. Taking its cue from Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, the CBC billed the budget as an historic break with the political legacy of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher and a return to the days when governments primed the pump and brokered social compromise.

As the CBC reports, this budget promises $135 billion in new spending over the next five years, the lion’s share destined to revive the economy from the pandemic-induced downturn. There is also new federal spending planned for 2025-2026 to the tune of $16.1 billion along with an array of social initiatives, including $8.4 billion for early learning and child care, $3 billion for Old Age Security, $2.5 billion for public transit and $1.9 billion for climate change and the environment. Acknowledging that “Low-wage workers in Canada work harder than anyone else in this country, for less pay” and that “many live below the poverty line, even though they work full-time,” Freeland touted the expansion of the Canada Workers Benefit as the key to lifting 100,000 people out of poverty.

Writing in Canadian Dimension, Christo Aivalis offered a rather more subdued appraisal of the budget, concluding that it “fails to meet the needs of Canadians during the greatest crisis facing this country since the Second World War.” He pointed out that budget blueprints are far from certain to be implemented and that empty Liberal promises on child care have a history that spans generations. He drew attention to the glaring omission of a desperately needed pharmacare program. He also, tellingly, reminds us that much of what is offered rests on provincial governments choosing to buy into the initiatives. Putting this interventionist turn into perspective, Aivalis noted that the full cost of Liberal military commitments is actually ten times greater than the proposed allocations for child care.

Yet, notwithstanding the need for a realistic and cautious examination of the Liberal budget, no one can pretend that it is a continuation of what we had come to expect prior to the pandemic. It marks something of a change of direction, delivered in an international context in which governments have been driven to shift the emphasis from deficit reduction towards economic stimulation. In the US, the Biden restoration has introduced major measures of this kind that have been presented by the media in terms that are just as extravagant and glowing as those hailing Trudeau’s initiatives. Beyond this, Biden is moving towards very considerable measures on infrastructure renewal, with a $2 trillion plan for the “most resilient, innovative economy in the world.” The IMF is also advancing notions of a kinder, gentler capitalism. Last year, its managing director spoke of “a new Bretton Woods moment” and even offered up a vision of a “sisterhood and brotherhood of humanity.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland before tabling the federal budget at the House of Commons in Ottawa, April 19. Photo by David Kawai.

Economic stimulation

We might be forgiven for suspecting that a love for humanity is not the driving force behind these developments. The US and its junior partners, including Canada, are taking up their restorative efforts with a nervous eye to their global rivals, especially China. It was Liberal military spending that paid for a Canadian warship to sail into a disputed area in the South China Sea recently, in a deliberately provocative act. Economic slump and crumbling infrastructure are alarming prospects in the face of the growing economic power and global reach of China. Regardless of the motives, however, the question to grapple with is whether the post-pandemic period is likely to produce a fundamental break with the decades of neoliberal austerity and a new approach that is much closer to the deficit-financing and relative social compromise of the post-war years.

There is no doubt that, with uneven levels of commitment and effectiveness, capitalist states have been forced to respond to the pandemic crisis with such measures as physical distancing, economic shutdowns and increased social provision. This reflects the obvious fact that profit-making becomes impossible in conditions of public health breakdown and major social dislocation. Now, with the pandemic far from over and its future course uncertain, the slump and the “economic scarring” that will remain once it is finally under control, bring home to all but the most dull-witted political leaders the need for measures to revive flagging economies. It is one thing, however, for this approach to be adopted in the short to medium term and quite another for it to be taken up as a dominant and sustained policy approach.

The post-war settlement that emerged in the late 1940s and continued for some two and a half decades, saw workers’ rights and living standards greatly enhanced and outlays on social spending very considerably increased. As a long economic boom unfolded, this was a period of relative class compromise that nonetheless saw very high rates of business profits. The neoliberal turn in the 1970s was primarily driven by a decline in profits due to the very concessions that had been made to the labour movement. The decades that followed were devoted to an effort to restore profitability through increased exploitation. Though they did not rise to the post-war levels, profits were resuscitated during this period.

The financial crisis and the Great Recession of 2007-09 put an end to this revival. The years after this were marked, moreover, by a remarkably sluggish recovery with low levels of profitability and dismal levels of productive investment. The low interest rates and quantitative easing that were adopted to keep things afloat produced an asset bubble but didn’t restore the health of the “real economy.” Further, as Marxist economist Rick Kuhn has pointed out, “For at least a year before the pandemic, global growth was slowing; the world economy was already moving towards another recession.”

Thus, while it massively intensified the depth and scale of the economic downturn, the pandemic descended on a global economy that was already in trouble and subject to long term contradictions. In terms of the prospects for a post pandemic recovery, Michael Roberts draws attention to the viewpoint coming from the US Federal Reserve that, “the US economy [is] going to have a ‘sugar rush’ from the fiscal stimulus and from the ‘pent-up’ demand of consumers but the Fed worries that “after this burst of energy on the ‘sugar high’ of government paychecks and restaurant meals, the US economy will slip back into the low growth trajectory that applied before the pandemic slump.”

People wearing surgical masks walk in East London. Photo by Alberto Pezzali.

Roaring Twenties?

In another article, Roberts looks at the severely limited prospects for a reprise of the Roaring Twenties in the coming years. He suggests that, even if the formidable problems that have been created by the pandemic can be overcome, there are no grounds to expect a rise in profit levels or a major sustained expansion of economic growth. The basis for this would have to be the “creative destruction” of capital that precipitated previous upturns, like that of the 1920s and the post-Second World War period. This didn’t happen during the years of sluggish recovery and it hasn’t happened yet during the pandemic slump. The low interest rates and other measures that have averted disaster have led to the rise of unprofitable “zombie” companies, kept afloat by these measures. “The latest data,” Roberts observes, “show that in the US nearly 20 percent of all firms are in the ‘zombie’ category, while in Europe it is as high as 40 percent. That is not the capitalist recipe to start a long boom.” Over and above this, if we take into account the pandemic-intensified debt crisis facing poor countries and the rapidly accelerating impacts of climate catastrophe, the prospect of such a sustained period of growth looks even less likely.

The key consideration that emerges is how the left should orient itself in the period that is now opening up. I would argue that it is wrong to assume from the policy shifts we see from the Biden Democrats or the Trudeau Liberals that the leopard has changed its spots. The concessions that employers and states make aren’t driven by wishes and hopes; they hinge, first and foremost, on the ability and willingness of those in power to provide them. The post-war Keynesian approach was based on a capacity to broker social peace, while ensuring a robust flow of profits. There is no such prospect before us at present.

The second main factor that determines the scope of the concessions that will be made is, of course, the magnitude of the struggle taken up by working class movements. The fights that we wage can make a decisive difference in this regard. However, the terrain on which these conflicts will play out is not one that lends itself to social compromise. There is no golden age of reciprocity ahead. The capitalist system is in crisis and a capacity to rebound and broker peace deals is lacking. The question of who pays for the crisis will not be settled by enlightened policies from on high but through the class struggle.

John Clarke is a writer and retired organizer for the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP). Follow his tweets at @JohnOCAP and blog at johnclarkeblog.com.