A common language: Critical metals and Québec’s clientelist relationship with France

François Legault is embracing a greenwashed future of critical metal dependency and multinational corporate monopolies

Québec Premier François Legault is joined by industry leaders to break ground on the construction site of a new Ford Canada manufacturing plant for electric vehicle battery material in Bécancour, August 17, 2023. Photo courtesy Gouvernement du Québec/X.

Visiting Canada and Québec on his first trip outside Europe since his appointment in January, French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal participated in an exchange with Québec Premier François Legault hosted by the Chamber of Commerce of Metropolitan Montréal (CCMM) on April 12. France’s youngest-ever prime minister emphasized the historic and cultural ties between France and Québec and stressed their singularly close relationship.

France is the second-largest importer of Québec goods after the US, with exports last year valued at $2 billion (CAD). In coming years, Québec is expected to serve the needs of the French energy transition along with the demands of the European consumer market. The France 2030 investment strategy earmarks €5.6 billion for the reduction of carbon emissions from heavy industry and is intended to help France attain carbon neutrality by 2050.

Attal and Legault’s meeting took place in the wake of the French senate vote against the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) in March. While the agreement has received official support from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and French President Emmanuel Macron, it has been contentious in France amid months of farmers’ protests that have been motivated in part by unfair competition from cheaper foreign imports.

Attal and Legault’s meeting on the energy transition, critical metals and the development of the EV battery sector reflected the desire of the French and Québec governments to push forward on the free trade deal.

“Today we are in the process of rebuilding our economic models,” the President of the French Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Canada, Francis Repka, stated. “Québec can and should strengthen its position as a gateway to North America for French businesses.”

“Québec businesses can and should take advantage of France as an investment platform to access the most important market in the world, the European Union.”

Laying the foundation

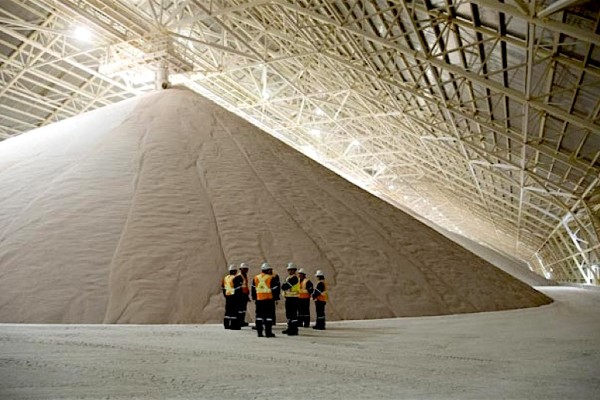

Leaning on a historic legacy of colonial single-industry towns built around the mining sector in the 19th and early 20th centuries, many regions of Québec are now being developed for the new era of critical metal dependency. The meeting between Attal and Legault revolved around a vision of Québec as a nucleus for the full lifecycle of a rechargeable battery along the entire supply chain: from lithium mining through refining and production to the recycling of EV batteries.

Québec is expected to see greater integration of French multinationals in the province’s battery industry and the renewable energy sector at large.

This includes Waga Energy, and its Shawinigan-based subsidiary Waga Energy Canada, a biomethane producer with numerous projects rapidly expanding across Canada and Europe converting landfill gas to renewable natural gas. In Chicoutimi, for example, the French multinational sells biogas from a local landfill to Québec energy company Énergir. But French corporations are interested in more than landfills in Québec’s aluminum heartland.

Prior to the public address of Attal and Legault, an industry panel representing Québec and French corporations discussed regionalization and supply chain diversification for the rechargeable battery sector. Apart from Waga, executives hailed from Montréal’s Lithion Technologies, the Vallée de la transition énergétique in the Trois-Rivières region, and French investment company Tikehau Capital.

As Québec gears up to be transformed into a North American battery hub, “innovation zones” are a key piece in the sector’s development. The Québec government has established innovation zones in a bid to “revitalize the industrial sector” by building infrastructure for research and development in dedicated regions, like the DistriQ quantum science innovation zone in Sherbrooke.

Announced in May 2023, the Vallée is Québec’s third innovation zone, tying together projects in Trois-Rivières, Shawinigan and Bécancour. The CAQ dedicated $8 million (CAD) to the development of seven projects in this region, in addition to Ford’s EV battery plant, and the GM and POSCO Ultium CAM cathode factory currently being built.

The Vallée will incorporate the existing mining industries in the region, like Nemaska Lithium and Nouveau Monde Graphite.

Montréal’s south shore, on the other hand, is expected to play a key role in the battery recycling sector.

Lithion Technologies, a lithium-ion battery recycling company based in the Anjou borough of Montréal, is building its first commercial plant in St-Bruno-de-Montarville. The plant would extract critical minerals from batteries sourced from Canada and the US to serve a global battery recycling market that is swelling to an expected value of $36.80 billion (USD) by 2032.

Though Legault and the corporate executives at the meeting with French PM Attal talked vaguely about high environmental standards, there was no mention of pollution like groundwater contamination with carcinogens and heavy metals caused by mining for “white gold” produced by lithium refining plants. There was no mention of long-term health impacts on mining or factory workers, or on residents in areas close to battery plants. There was no mention of the pollution caused by consumer supply chains or the basic consumption patterns encouraged by mega-corporations that drive the demand for rare earth elements and batteries.

And amid all the emphasis on the regionalization of the EV battery supply chain, there was no acknowledgement of the territorial rights, let alone economic agency, of Indigenous communities across Québec.

The Prime Minister of France Gabriel Attal, left, and Québec Premier François Legault hold a meeting to discuss trade and strengthening the French language, April 11, 2024. Photo courtesy François Legault/X.

Public-private ambiguity

Buoying the development of Québec’s battery plants is a wave of corporatization in the public research sector and a preferential immigration process, bespoke for white-collar workers from France.

“We need to commercialize our research,” said Legault. “When it comes to basic research, we are among the best in the world… But when it comes to commercializing research, we are among the worst in the world.” Legault emphasized the need for a change of culture “to be able to innovate with innovative products.” He sees innovation zones like the Vallée as the way forward: physical spaces where “there are no barriers” between researchers and corporations like GM and Ford. Legault referred to German and Swedish models in which researchers from public universities are brought into private corporations to help them develop new products.

The corporatization of academic research is well entrenched in Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean, a region beholden almost exclusively to the interests of British-Australian multinational Rio Tinto.

In Saguenay, Rio Tinto has a hand in financing virtually every aspect of economic development, including public research at the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (UQAC). One such project is the company’s 25-year R&D partnership on bauxite processing as the company looks to profit from toxic bauxite dust created in the aluminum manufacturing process, as well as researching other uses for residue.

Rio Tinto has also been testing “zero-carbon” aluminum technology called ELYSIS at the smelter in Alma. The proprietary technology behind Québec’s claim to “green aluminum” was developed with federal and provincial funding as well as $13 million (CAD) in financing by Apple.

Corporate financing of public-private partnerships, however, gags researchers with non-disclosure agreements and normalizes corporate loyalty for academics employed by the public sector. Research and technologies that could help society combat the climate crisis are publicly subsidized but serve private interests.

At their meeting, Attal and Legault both talked about attracting workers to factories and creating white-collar jobs, auguring changes to the immigration system. Executives on the economic panel preceding the PMs’ exchange referred to Québec’s long and expensive immigration process, and the need to fast-track it for French immigrants. Legault explicitly mentioned the need to make the immigration process easier for France.

These calls for built-in favouritism came only weeks after Québec’s Immigration Minister Christine Fréchette said that Québec is near a “breaking point” with asylum seekers. It so happens that many of them are fleeing countries ravaged by war and famine stoked by critical metal mining and battery supply chains.

Industrial-scale cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), for example, are notorious for using child labour, slavery, and exploiting migrant workers. With the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, over 70 percent of the cobalt used in rechargeable batteries comes from the DRC.

Forced evictions resulting from the corporate takeover of Congo’s land for cobalt and copper mining have included the expulsion of residents from the city of Kolwezi and the destruction of homes, schools and hospitals across the country deemed to be located on mining concessions. Among the human rights abuses perpetrated by multinational companies in the country, Vancouver-based Ivanhoe Mines has been implicated in the eviction of dozens of families for its subsidiary’s Kakula copper mine.

The displacement in the DRC caused by the rechargeable battery industry has contributed to a crisis that sees 5.6 million internally displaced people living in refugee camps and flimsy tarp shelters across the country—a population that is around three times the size of Montréal. Evictions by mining companies grasping at Congo’s cobalt and copper have exacerbated a humanitarian crisis that has been worsening amid escalated armed conflict, with nearly a million people from the DRC seeking refuge elsewhere on the African continent.

Today, the DRC is among the five main countries of origin for asylum-seekers staying in Québec since the closure of Roxham Road in March 2023. As Québec shrugs off asylum-seekers from the most vulnerable populations impacted by global demand for rechargeable batteries, the lavishing of privileges on French corporations, including fast-tracking immigration from France, reflects the lack of humanitarian commitment and compassion driving Québec government policy.

The Whabouchi mining project, operated by Nemaska Lithium, is located 30 kilometres from Nemaska and 280 kilometres north-northwest of the municipality of Chibougamau, Québec. Photo courtesy Nemaska Lithium.

Neocolonial energy sovereignty

Despite widespread disapproval of CETA in France and Macron’s anti-democratic push for its adoption, Attal and Legault were adamant about the “common values” of free trade as central to the “green energy transition.” Moreover, the geopolitical motivations behind France’s incursion into Québec’s natural resource and emerging battery sector reflect a new era of resource colonialism masquerading as energy sovereignty.

Driven by critical metals industries in Australia, Europe and North America, this new wave of resource colonialism has spurred some countries to adopt protectionist policies that threaten the interests of multinational corporations. A case in point is Namibia’s ban on the export of unprocessed rare earths like lithium.

Especially given US exclusionary regulations that shut out companies with stakeholders from China, Iran, North Korea, or Russia holding over 25 percent of the shares of a company, Québec is a competitive alternative with its growing domestic sector in rare earths and battery production.

Even with Chinese lithium being excluded from battery supply chains, foreign raw materials need to be shipped to be refined and processed, including to South Korea for battery manufacturing and separate recycling facilities. Regionalization in the critical metal supply chain would cut down on major global transport.

For France, it would also mean fewer diplomatic hassles.

Attal echoed the slogan of “energy sovereignty” and resilience in the supply chain, a key point in France’s public relations strategy on the energy sector’s shift toward dependency on critical metals. He commented on Moscow’s blackmail of countries that are dependent on Russian gas.

But France’s transition away from fossil fuels is not just driven by Russia’s war in Ukraine. TotalEnergies was also burned by the economic sanctions imposed on Myanmar following the coup in February 2021. The French company exited Myanmar in July 2022, selling its stakes in offshore oil and gas in Rakhine State amid the country’s civil war. This is despite years of human rights abuses against the state’s Rohingya population.

France’s current pursuit of diversification in the energy transition and its quest for critical metals has recently taken it to the halls of parliament in Ulaanbaatar. A €1 billion agreement on uranium mining was struck between France and Mongolia this past October, giving the French nuclear corporation Orano access to deposits in the Gobi Desert, alongside a lithium exploration license for the Dornogobi province.

For Macron, access to Mongolian uranium and lithium is key to “our energy sovereignty,” as France is currently the largest energy exporter in Europe. But Ulaanbaatar’s administration is dealing with the competing interests of neighbouring China and Russia, as well as those of NATO states. In the wake of Nord Stream’s sabotage—deemed intentional by Swedish investigators—and the loss of Total’s fossil fuels assets in the Indian Ocean, France’s vision of energy sovereignty simply shifts the axis of dependence to find natural affinity in Québec.

Legault ended the exchange with Attal by returning to the French language as a bond between French and Québec corporations. He stressed that, in the current context, it’s important to be able to work with allies who have similar values and standards, “and maybe give each other a little preferential treatment over those countries that aren’t on board with decarbonization.”

Certainly, France and Québec are aligned in paternalistic and anti-democratic policy like Macron’s inveteracy on a popularly-opposed CETA and Legault’s own recent adoption of Bill 15 that mobilized protests from striking public sector workers across Québec.

Québec’s ambitious strategy for regional development across the entire lifespan of rechargeable batteries proposes real benefits in a challenging transition away from fossil fuels and dependence on conflict resources, but at what cost? As the meeting between Attal and Legault shows, Québec’s future is being shaped to cater to big capital: swapping the blueprint of the fossil fuels industry and the “circular economy” of petrochemicals for a greenwashed future of critical metal dependency and multinational corporate monopolies branded as “green energy” innovators. In Montréal, the colonial echo of la Francophonie resonated with the grammar of greenwashed free trade.

Lital Khaikin is a freelance journalist and author based in Montréal, and regularly contributes features on humanitarian and environmental issues related to underreported regions and conflict zones.