1919: Recovering a legacy

To orchestrate mass resistance effectively, labouring people need the guidance and perspective of an organized left-wing

Illustration from 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike by the Graphic History Collective and David Lester (Between the Lines, 2019).

When the world watched Winnipeg

Alexander Bittelman, a Jewish immigrant and leftwing activist in New York’s Socialist Party, recalled the impact of the Winnipeg General Strike in May 1919. “The feeling of an approaching storm was especially aroused” in his circles, where the Canadian events were much discussed as part of “the widespread strike struggles” unfolding as “the left wing was taking shape.” There were “eloquent indications that things were coming to a showdown.” According to Bittelman, militants prepared themselves to “take the lead,” creating organizations that might bring about the much-heralded new dawn of the workers’ revolt.

In Glasgow, the “Scottish Lenin,” John Maclean of “Red Clydeside,” saw “the great Canadian strike” as nothing less than “class war on an international scale.” For Turin’s Factory Council Movement, and the socialist group around the journal L’Ordine nuovo (The New Order), Winnipeg elicited similar commentary. Antonio Gramsci saw the Canadian uprising as part of a new “Revolutionary Tide,” a “world-scale” tsunami that promised the realization of “a Soviet regime.”

Commentators in leading U.S. newspapers seemed to agree. Chicago’s Daily Tribune headlines declared: “All Winnipeg Under Rule of Strikers.” New York Times editorials bemoaned that strike fever was “sweeping [the] West.” For these journalists, the General Strike, “an attempt at Revolution and an imitation of Soviet Autocracy,” represented nothing less than a “beautiful demonstration of essential Bolshevism.”

The struggle unfolds

The 1917 Bolshevikled

October Revolution

inspired working and

oppressed peoples

throughout the world.

This early Soviet poster

circa 1920 depicts

Lenin sweeping the

globe of capitalists,

monarchs and clerics.

Tensions mounted as bosses and their organized business associations dug in their heels in reaction to class resistance. The arrest of a militant worker, revelations that employers were paying labour spies to report on union meetings, and rumours that the government was bankrolling agents provocateurs upped the conflictual ante.

At a 13 May 1919 Trades and Labor Council meeting, Winnipeg’s organized workers heard that the city’s unions voted 11,000 to 500 in favour of declaring a general strike. Bob (R.B.) Russell, a leading figure in the Canadian Pacific Railway unit of the International Association of Machinists and an ardent socialist, anti-war advocate, and later campaigner for the One Big Union – urged workers to take “no more defeats.”

Mass walkouts commenced 15 May 1919. Within days 35,000 Winnipeg workers were on strike and Winnipeg’s population of 175,000 was polarized. Many of the strikers were non-English-speaking immigrants. They were not affiliated with the powerful craft unions made up of skilled workers of British descent whose discontents first sparked labour walkouts. But immigrant communities were linked to the “respectable” Anglo-Canadian leadership of the strike through common sensibilities, especially evident in overlapping networks of socialist publications and associations.

Winnipegitis

Winnipeg’s general strike, and the need to defend it against attack, resonated with workers across Canada. A wave of sympathetic strikes rocked the country. The body politic reacted as though it was being attacked by a disease, which was soon demonized with the designation, “Winnipegitis.” In a brief three-month period, from May to July 1919, 210 workplace walkouts took place in Canada, involving 115,000 men and women. The radical leader of the Nova Scotia miners, J.B. McLachlan, called on the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada to organize a nation-wide general strike to defend the freedoms of speech and association of the Winnipeg strikers.

Women, if they were not striking themselves, were often sustaining militancy through Women’s Labour Leagues. Even before the declaration of the Winnipeg General Strike, the federal government, cringing in anticipation of a labour uprising, established a Royal Commission on Industrial Relations to be chaired by Manitoba’s Chief Justice, T.G. Mathers. In travelling the country as the 1919 strike wave peaked, Mathers heard startling testimony from working-class women. They complained of inadequate and unsanitary housing, rampant inflation that eroded their capacity to feed children, and the abysmal wages of women employed outside the home.

Saskatoon’s “Miss” Francis, testifying to Mathers, insisted that “plundering must cease” and “profiteering must go.” The “larger hopes of the people” had to take precedence over the moneyed interests argued Francis. She concluded “production for use” must replace “production for profit.” Rose Henderson of Montreal told the Mathers Commission that “the real revolutionist is the mother – not the man. She says openly that there is nothing but Revolution.”

Radical Winnipegitis advocates soon faced the opposition of their conservative counterparts within the upper echelons of organized labour’s bureaucracy. The Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees head, Aaron Mosher, got in on the anti-general strike act. He volunteered his services to Prime Minister Borden, noting that his trade union members were striking even after official authorization had been denied them. “The rank-and-file in the labour movement,” Mosher claimed, were “forcing the leaders to take the stand they have taken.” An American Federation of Labor (AFL) official complained that the militant workers of the Canadian west wanted “nothing short of a transfer of the means of production … from that of private control to that of collective ownership.” Winnipegitis was a plague on both the Bourgeois House of Order and the Officially- Recognized House of Labour.

May 26, 1919; Alberta

newspaper announces

Edmonton general

strike in solidarity

with Winnipeg strikers.

The state and capital on alert

Capital and the state recoiled from the escalating class conflict of 1919’s Winnipegitis in fear and loathing. Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP) reports indicated that returned soldiers were lining up behind the socialists. A “Memorandum on Revolutionary Tendencies in Western Canada” warned of a general state of “restlessness and dissatisfaction.” Left-wing agitators were the “foam on the wave” of an “uncertain, apprehensive, and nervous” proletarian temper that was growing more threatening by the day. If the state would pass appropriate legislation, RNWMP Commissioner Aylesworth Bowen Perry was prepared to deport “one hundred dangerous aliens” in early June 1919, taking the revolutionary wind out of the defiant sails of Winnipeg’s insurgent workers.

Banded together in a Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, Winnipeg’s elite peppered politicians like Borden, the Minister of Labour, Gideon Robertson, and the Acting Minister of Justice, Arthur Meighen, with appeals to save Canada from the supposed Bolshevik Revolution that gripped Winnipeg. Nothing drove the patrician Committee to exasperation more than the general strikers flaunting their power.

The General Strike Committee issued cards of passage through the city for milk wagons and other deliveries of essential services, authorizing everyday business transactions. As a concrete expression of how the world was turned upside down in May to June 1919, the posted declaration that some activity had been “Permitted by Authority of the Strike Committee” proclaimed a proletarian order that defied conventional capitalist relations.

The Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, proudly naming itself as the one per cent, demanded an end to the presumptuous rule of workers. A return to private property-based governance was demanded. If this took an influx of troops, declarations of martial law, amendments to the Criminal Code, deportations of all radical aliens, mass arrests, and state trials – so be it.

Winnipeg Strike

Committee; photo

by L.B. Foote; Archives

of Manitoba, Courtesy

of Sharon Reilly.

Deadly denouement

Much of this happened. Robertson dismissed the striking postal workers who refused Ottawa’s dictate that they return to work. Almost 250 city cops were fired for sympathizing with the strikers. The Citizens’ Committee assembled a force of “special police” – over 1,000 strong – to patrol the streets. Riots ensued.

Meighen condemned the “revolutionists of various types, from crazy idealists down to ordinary thieves.” His paranoia about “Bolshevism” and “Socialism” running rampant throughout Canada was legendary. He even called on the British government to station a warship off Vancouver to serve as a “steadying influence” on the turbulent politics of the immediate post-First World War period.

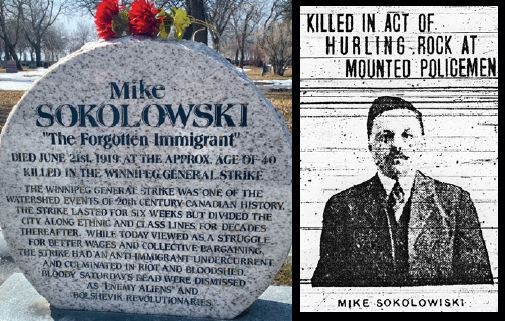

Ukrainian-born

labour martyr Mike

Sokolowski’s headstone,

placed in

2003 at Winnipeg’s

Brookside Cemetery.

The “anti-immigrant

undercurrent” cited

in the inscription was

in fact a torrent of pro-

Empire anglo racism,

unleashed against the

strike by the bosses

and their state. The

“riot” was an organized

police assault intended

to spill strikers’ blood.

After six weeks of struggle, and with the Citizens’ Committee calling the shots and federal power decisively arrayed against the strikers, the massive walkout ended on 26 June 1919. The Central Strike Committee urged Winnipeg’s workers to “speak in no uncertain terms at the next municipal election.” A worried Trades and Labor Congress organizer breathed a sigh of relief that the Winnipegitis epidemic had been quarantined. Labour’s defeat was, he hoped, an inoculation against the threatening disease of revolutionary industrial unionism. “There never was in history a strike in which the workers answered the call so spontaneously,” he wrote, “and there never was a strike in which the workers were so badly trimmed.”

Arrested strike leaders

awaiting trial, 1919.

Back row, left to right:

Roger Bray, George

Armstrong, John

Queen, R. B. Russell,

R. J. Johns, William

Pritchard. Front row:

William Ivens, A. A.

Heaps. National

Archives. Courtesy

of Sharon Reilly.

Tribunals and trials

With the Immigration Act compliantly revised by the federal state to allow for deportation of “foreign born” strikers without trial and without evidence justifying banishment, the persecution was largely in the hands of the head of the Citizens’ Committee, A.J. Andrews. A number of immigrant workers arrested on “Bloody Saturday” found themselves whisked off to a northern Ontario camp in Kapuskasing to await transportation to Germany, Russia, and elsewhere. Four ostensibly “dangerous foreigners” were arrested (a fifth was also taken into custody and fairly quickly released), three of whom were Eastern European Jews, Samuel Blumenberg, Solomon Almazoff, and Michael Charitonoff, while Oscar Schoppelrei was German. Blumenberg, a Socialist Party of Canada militant, was well-known for sporting red ties that matched his anti-war, pro-Bolshevik views. As an agitational dramatist, Blumenberg wrote a number of plays, among them Undesirable Citizen.

Imprisoned without bail, the four radical “aliens” were eventually brought before the Immigration Board. A vigorous defence campaign was conducted, but Schoppelrei, Blumenberg, and Charitonoff were ordered deported. The latter secured a reprieve through appeal. Blumenberg apparently cheated the state of its power to deport, making his way to

the United States, leaving only Schoppelrei to be formally exiled.

Ten English-speaking, British-born strike leaders – James S. Woodsworth, Bob Russell, William Ivens, Abraham A. Heaps, Roger Bray, George Armstrong, John Queen, William Pritchard, R.J. Johns, and Fred Dixon – were ultimately charged by the state with either seditious conspiracy to overthrow the government or, in the singular case of Dixon, seditious libel. The state trials, conducted over the last half of 1919, resulted in three acquittals (Woodsworth, Dixon, and Heaps) and seven convictions, carrying sentences ranging from six months to two years.

Labour defence

The trials led to the formation of a Winnipeg Defence Committee. This Committee initiated a convention of protest. Six hundred delegates undertook legal appeals, to sustain the families of their incarcerated comrades with monthly payments of $35 and to continue to propagandize about the Winnipeg General Strike and its meaning.

Out of this campaign came the publication and dissemination of crucially important documents, including the strikers’ own history, Saving the World from Democracy: The Winnipeg General Sympathetic Strike (1920), and W.A. Pritchard’s Address to the Jury (1920). The latter was a transcript of Pritchard’s two-day courtroom statement. It laid bare the analytic foundations and political commitments of the revolutionary socialists who found themselves on trial. They had not, of course, led a revolution, in spite of what the world watching Winnipeg and the many inside and outside of Canada thought. Pritchard knew this well, appreciating that, “Only fools try to make revolutions, wise men conform to them.”

The mundane and the militant

Conservative historians have long held that the Winnipeg General Strike was nothing more than a collective bargaining dispute gone wrong. Fought out over mundane issues of work and wages, the May-June conflict was elevated to a Bolshevik insurrection by self-serving capitalists and politicians who had panicked. Radicals were an irksome thorn in the overly tender side of a regime of acquisitive individualism.

This is true enough as far as it goes. Yet it misses much. Winnipeg 1919 showed how the logic of adversarial class relations led from the mundane to the militant. Objective conditions exacerbated the level of antagonism between irreconcilable interests and a revolutionary subjective element was present and in a position to guide the unfolding conflict. It was not a revolution, but the prospect of revolutionary struggle and transformation seemed possible. Organs of opposition, like Vancouver’s Red Flag, discussed how, as general strikes unfold, they throw up the necessity of creating institutions of dual power, “displac[ing] the capitalist government which operate[s] for the benefit of the bourgeoisie.”

The general strike in Winnipeg proved how a fusion of the industrial struggle with an oppositional politics could threaten the bourgeois order and nurture visions of socio-economic transformation and the creation of an alternative society. It could not have happened had class antagonisms not pushed masses of workers to militant strike action. But the conflict would not have gone as far as it did had there not been a contingent of working-class leaders who saw beyond the limitations of “bread and butter” trade union demands to a “golden future” in which, as the socialist writer Jack London expressed it at the time, there would be “no servants, naught but the service of love.”

1919: Then and now

How far have we come since 1919? Quite a distance would have to be the understated answer. The labour movement is in pronounced retreat. Since the mid-1970s capital and the state have been on the offensive. With the aggressive rise of the Right, the entitlements won by labour in the aftermath of the Winnipeg General Strike have been eroded to the point of evisceration. Real wages stagnate, union densities are in decline, and annual strike levels plummet. The state has declared war on organized labour – legislating workers who have the temerity to strike back to their jobs. The yearly number of Canadian strikes in the 1970s might reach 1,000. More recently, annual figures rarely exceed 200. In 2018, the official tally of Canadian strikes was a meagre 62 involving barely 22,000 workers.

Where is the talk of general strikes today? Quebec’s working class launched an impressive general strike in 1972. There was at least an audible hint of militancy in the willingness by the Canadian Labour Congress to mount a so-called one-day country-wide general strike to oppose Pierre Trudeau’s announcement of a government policy of wage and price controls in the mid-1970s.

By the 1980s and 1990s, labour movement calls for general strikes were more blustering brinksmanship than genuine class struggle calls to the barricades. In British Columbia’s Solidarity uprising of 1983 and in the Ontario Federation of Labour’s campaign against Mike Harris’s Common Sense Revolution in the late 1990s, staggered strike actions and protests promised to culminate in general strikes. In the end, nothing of the sort happened. The trade union leaders backtracked and threw in the towel.

Even the once militant Canadian Automobile Workers (CAW) union – which unleashed a series of plant occupations and pioneered flying squadrons of activists to support strikes and social movement campaigns outside of its ranks over the course of the 1980s and 1990s – is quiet in the face of the automobile companies’ offensive. Negotiating two-tier contracts that codify reduced wage, benefit, and pension terms for younger hires, CAW has succumbed to bosses’ concession demands that years ago it would have taken job action against. The announcement that Oshawa’s General Motors plant will close, bidding adieu to thousands of jobs, is met with lots of trade union officialdom bravado, but the rallying cry now promoted is the boycotting of made-in-Mexico cars. Such an ineffectual protest only drains the potential of building militancy into union activism.

This disturbing reality is a reflection of the demise of the labour movement. It also grows out of the decline of the revolutionary left. At no point in time over the course of the last 100 years has this organized revolutionary left been weaker. We simply do not have modern-day equivalents of the Socialist Party of Canada agitators, One Big Union campaigners, and ethnic, Social Democratic Party-affiliated socialists who constituted the strike leadership in 1919, many of whom went on to found and lead the Communist Party of Canada in the 1920s and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation of the 1930s.

With the implosion of the 1960s New Left and its successors in the new communist movements of the 1970s succumbing to an array of internal dissensions and the “dirty tricks” of the state and its “intelligence” operatives, the revolutionary left’s demise in Canada parallels the free fall of trade unions and their ossified bureaucracies in the age of austerity. Stalinist Communism’s collapse has exacerbated this process of decline. The Right is now, largely, in command of both the political culture and the political economy. Organized labour and the Left are in retreat, to the point that the latter threatens to disappear from view, while the former is reduced to a baffled accomplice in its own enervation.

The Red Flag,

June 14, 1919; newspaperarchives.

com.

Recognizing a legacy

For decades after 1919, the workers’ defeat of that year was celebrated, not as a drubbing, but as the articulation of democracy’s potential. The 41-day strike witnessed 171 mass meetings – expressions of participatory democracy that would be heralded by 1960s youth as a New Left antidote to the limitations of parliamentary elitism. Bill Pritchard noted that the strike itself had commenced democratically: “The workers stood for open discussion and decision by ballot. That was how this strike was called.” It was not an autocracy, Soviet or otherwise, in spite of the characterizations of the powerful who resented this democratic practice exercised from below.

In the aftermath of the General Strike, the politics of labour turned defeat into polling victories. The Conservative Party, led by Arthur Meighen as of July 1920, soon lost every electoral district in the Canadian west, including Meighen’s Portage la Prairie, Manitoba seat. Five of the strike leaders arrested in 1919 ran successfully in the next federal and provincial elections, three of them campaigning from jail cells. Municipal, provincial, and federal elections in Manitoba were for decades influenced by 1919’s class politics. As late as 1969, with the New Democratic Party’s provincial victory, 17 of the 29 elected social democrats came from Winnipeg constituencies, with some of those elected being descendants of the General Strike participants.

From 1919 to our present day, Winnipeg proclaims that there is no dishonour in struggling to win and losing to a powerful foe who holds many cards drawn from a stacked deck. The larger dishonor is in the failure to fight. Defeats growing out of struggle, like the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, can live on as victories, examples of stands taken on the battleground of class resistance.

Recovering the legacy

Winnipeg in 1919 has taught us many lessons. One of these was that the power of militant workers can only be marshalled, sustained, and turned to victorious purpose by a steeled and socialist leadership. Rank-and-file resistance can spontaneously erupt but it inevitably faces the concerted opposition of capital and the state. To orchestrate mass resistance effectively, labouring people need the guidance and perspective of an organized left-wing.

This leadership will not be generated out of the trade unions as a matter of instinctual course, as it was not in Winnipeg in 1919. As legal institutions within capitalism, trade unions are constrained and even controlled in ways that will always inhibit the rise of a class-struggle leadership. Such a leadership can never survive, even if it manages to surface in an individual figurehead. Leadership needs to develop consciously in ways that provide it a refuge and resources outside of the confines of trade unionism at the same time that it exercises influence within the institutions of the labour movement.

“Winnipegitis” can be brought back from the scrap heap of historically extinct afflictions targeting capitalism, where it has seemingly been dispensed with by the “science” of bourgeois regimes of exploitation and accumulation and the “iron heel” of the state’s repressive apparatus. This resurrection will only happen, however, through conscious effort. Such an audacious undertaking relies on a strategic pairing.

First, the unions, now increasingly stagnating and under the sway of conservative officialdoms, must be remade in the image of rank-and-file democracy and militancy. Left-wing caucuses inside the unions must promote general militancy, extending the struggles of the working class for better wages and conditions on the job into wider arenas of all manner of social justice campaigns. This struggle to rebuild the unions will necessarily create spaces for left leaderships to emerge and rise to positions of authority within the official labour movement.

Second, if this process is to deepen, however, both the rank-and-file caucuses and the left-wing trade union leadership they will nurture must inevitably rely on the expansion of the revolutionary left and the creation of the kinds of agitators who, similarly to those in 1919, ride the wave of spontaneous working-class rebellion. This will take place inside the unions, to be sure, but it must also happen simultaneously within many different kinds of social movements. All such activity will necessarily be orchestrated and analyzed within parties, institutions, mobilizations, and public sounding boards separate from both the unions and from an array of social movements addressing particular concerns.

Reclaiming the legacy of the 1919 general strike is a formidable task – one that will only happen if the unions and the Left are rebuilt in a reciprocal renaissance of the politics of opposition and class struggle. The prospects of either of these linked movements reviving alone, without the advance of the other, are slim indeed. Nor will these resuscitations occur if a host of other social movements, addressing issues of women, Indigenous peoples, racialized minorities, environmental degradation, and all manner of oppressions, are not engaged with seriously and sensitively. These coalitions of activists, moreover, need both the presence and the backing of strong and mobilized workers’ organizations and the revolutionary socialist Left.

Recovering and reclaiming the legacy of 1919 is, in 2019, challenging and complicated. Yet it is also desperately necessary. It may well be our only option.

Eminent labour historian Bryan D. Palmer is currently co-editor of Labour/Le Travail. He has authored many books including Canada’s 1960s: The Ironies of Identity in a Rebellious Era and is co-author of Toronto’s Poor: A Rebellious History (2017). He is a frequent CD contributor.

This article appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of Canadian Dimension (CD Goes Digital).