Ten years after the Marikana massacre, we must recognize Canada’s role in empowering mining companies in South Africa

Canadian companies did very well under the apartheid regime

Mourners attend a vigil for the victims of the Marikana massacre. Photo by Andreas Georghiou/Flickr.

On August 16, 2012, the South African Police Service (SAPS) opened fire on striking miners at the Marikana platinum mine, then owned by Britain’s Lonmin company. The miners, thousands in number, had declared a wildcat strike nearly a week earlier to demand a living wage, better housing, and improvements to health and safety. While some had armed themselves with handheld weapons such as spears and pangas (a large bush knife) for self-defence—several days earlier, their own union office had fired on them with live ammunition, killing two miners.

The miners were closed in with barbed wire and sprayed with bullets. Thirty-four miners were killed and 78 were wounded. Many of the dead and injured had bullet wounds in their backs. The police claimed they were defending themselves from violent rioters.

The Marikana Commission of Inquiry (also called the Farlam Commission) was first seated on October 1, 2012. Its final report, submitted on March 31, 2015, absolved the perpetrators and those accused of having a hand in the massacre, including current president Cyril Ramaphosa, who was a non-executive director of Lonmin at the time.

Ten years later, not one person has been arrested for the massacre. Families of the slain and injured are still organizing for justice. At a protest on August 16, 2022, a representative for the widows of those killed told a crowd of thousands, “We are still waiting to know the person who sent the police to kill our husbands.”

South Africa marked 10 years since the Marikana Massacre, when police killed 34 miners — the worst massacre since apartheid.

— AJ+ (@ajplus) August 16, 2022

They were striking for better pay from UK mining company Lonmin, which was paying its CEO £1.2M but workers just £306 a month.

No police were convicted. pic.twitter.com/gNqgnFRo3J

Photographs of the 34 miners killed by the South African Police Service during the Marikana massacre on August 16, 2012. Photo courtesy Economic Freedom Fighters/Facebook.

Mining is one of South Africa’s key industries. There are strong links between the global mining giants invested there and the South African state. Every year, South Africa hosts the Mining Indaba, a gathering of continental and international industry figures aimed at promoting the mining sector in Africa. The event is sponsored by some of the largest mining companies in the world, many of them Canadian.

Under the current economic order, South Africa’s mining wealth does not serve its national development. Much of the profit from large mines is invested outside South Africa by the predominantly white management class. As Mbuso Ngubane, Deputy General Secretary of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA), explained in a recent interview with People’s Dispatch, there is no state desire to use this wealth to improve South Africa’s manufacturing capabilities. Instead, the South African economy remains dominated by the service sector even though it is one of the largest mineral producers in the world, while the profits from these minerals fatten the pockets of transnational capitalists who have no interest in the working people who extract their riches.

In South Africa and other neoliberal societies, the workers who produce the surplus value are repressed while an isolated managerial class reaps the benefits of extraction. While there is no direct Canadian involvement in the Marikana massacre, Canadian mining companies and the Canadian state played a sizeable role in ensuring that the post-apartheid African National Congress (ANC) government did not radically restructure the economy for the benefit of the Indigenous black majority, and that they retained a favourable investment climate for foreign companies.

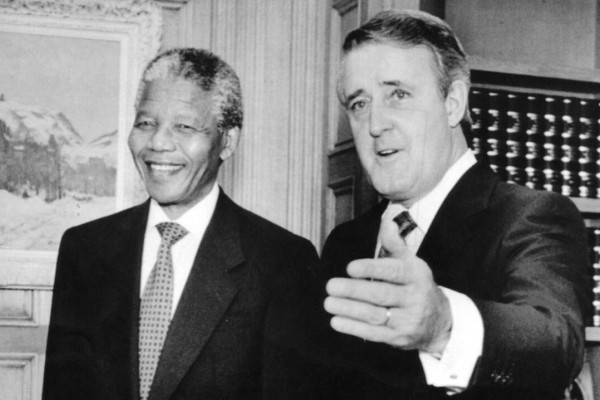

Throughout the twentieth century, Canadian companies did very well under the apartheid regime of South Africa. These companies included Bata Shoes, Hudson’s Bay Company, Ford Canada, and transnational miners Alcan, Cominco, Falconbridge, and Rio Algom. Their investments deepened throughout the 1970s, under the premiership of Pierre Elliot Trudeau, and continued to reap huge profits under his Conservative successor Brian Mulroney until Mulroney’s belated about-face in the 1980s finally aligned Canada’s position on apartheid with world opinion.

By the late 1970s, Pierre Trudeau could no longer ignore the shameless racial fascism of South African apartheid and implemented a series of measures supposedly designed to limit the involvement of Canadian business with the more sordid aspects of the regime. These measures included “the withdrawal of Canadian trade commissioners from Johannesburg and Capetown,” the cessation of Export Development Canada (EDC) funding for projects in South Africa, and the “publication of a ‘code of conduct and ethics’ regarding employment and related practices of Canadian firms doing business in South Africa.” The United Nations Centre Against Apartheid described these changes as “more cosmetic than real.”

When real support for the liberation struggle in South Africa did arrive in the form of Cuban troops, Ottawa reacted rancorously, with Pierre Trudeau stating that “Canada disapproves with horror [of] participation of Cuban troops in Africa” before cancelling Canada’s small aid program to Cuba. It would not be until 1979, by which point Cubans were fighting and dying alongside Angolans in the struggle against apartheid and Libyan advisors were supplying training and weaponry to the ANC, that Trudeau took the measly half-measure of ending preferential tariff rates with the South African government. Even this, as Yves Engler points out, “was as much an economic decision… as it was a reprimand for [South Africa’s] racist policies,” since at the time the trade balance between the two countries favoured the apartheid government.

Following the end of apartheid in South Africa, the IMF entered talks with the new government to, in its own words, “establish an outward-oriented economy.” Canada played its part to ensure that South Africa developed in the neoliberal direction. The head of External Affairs’ South Africa Taskforce stated that he hoped an International Monetary Fund (IMF) planning mission would enter South Africa so that the new administration would “get things right” in the beginning. In 1995, the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) funded the South Africa/Canada Program on Governance to provide “advice on issues ranging from how to improve service delivery… to how to link decision-making and budgeting.”

Canada’s role in preventing substantive economic reform in South Africa, and thus preserving the material base of apartheid, can easily be identified during the drafting of the new mining law. While the ANC’s 1955 Freedom Charter described a socialist vision of post-apartheid South Africa in which mineral wealth was nationalized, pressures from the white business class, international finance, and foreign companies (including Canada’s Falconbridge, which sent its legislative recommendations to the ANC) were instrumental in moderating the scope of new legislation.

Canadian embassy officials participated in the drafting of the mining law. A Canadian diplomat in Johannesburg stated that “the changes in the mining legislation have been a long time in coming and I do know that there has been substantial Canadian input.” In 2002, the South African magazine Mining Weekly revealed that, during the drafting of the bill, “Canadian enterprises were probably the foreign mining companies most consulted by the South African government… The South African government received a lot of input from the whole spectrum of the Canadian mining industry, from prospecting companies through mining houses all the way to analysts at the Toronto Stock Exchange.”

Canadian companies were clear about their disapproval of the redistributive direction of the draft bill. Firstly, the bill stipulated that companies seeking mineral exploration licenses had to give “historically disadvantaged South Africans” 15 percent of the company’s shares within five years. Moreover, the ANC’s promise to mandate 40 percent black management in mining enterprises worried companies which had long relied on South Africa for its cheap black labour source. Black management, they likely believed, would engender solidarity between workers and managers and disrupt the clear hierarchy that had proved so profitable to foreign capital in the preceding decades.

In March 2001, the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) wrote a 25-page criticism of the government’s draft bill in which they claimed that these new rules would “effectively bar” Canadian companies from operating within South Africa. In their response, PDAC also accused the new government of plotting to force Canadian prospecting rights to lapse so that “the [Mining] Minister could subsequently grant the right to historically disadvantaged persons.” Canadian companies Placer Dome and SouthernEra threatened legal action if any legislation infringed upon their mineral rights, an attack that could have cost the new South African government billions of dollars.

During this time, PDAC and a number of mining companies worked closely with the Canadian government to communicate industry concerns about proposed mining code changes to South Africa. This united front prompted the South African Minister of Mines to visit Canada and reassure the government that there would still be a place for Canadian capital in the new South Africa.

With the help of international financial institutions and white minority capital, the Canadian elite was able to get their way in South Africa. By the time the mining law was passed, its redistributive aspects had been watered down significantly.

The above-listed actions taken by the Canadian state against the new ANC government were instrumental in destroying radical redistributive measures and creating a post-apartheid economic paradigm in which the aims of private capital dominate and any organized workers’ resistance can and will be violently repressed. The Marikana massacre was an example of this paradigm—one in which mining giants can use their influence in the state to protect their massive extraction of surplus value from a brutalized working class—in action. In the words of NUMSA, it was “the first post-apartheid South African state massacre of the organized working class” in defence of “the local and international mining bosses and their profits.”

While the Canadian government frequently celebrates its supposedly principled stance against apartheid in South Africa, the historical record shows that Canada not only supported the apartheid regime for much longer than most countries, but also prevented any radical reorganization of the apartheid-era economy after the regime dissolved. In this sense, Canada helped create the economic and political context in which an atrocity such as the Marikana massacre, and the ensuing cover-up, could occur.

Owen Schalk is a writer based in Winnipeg. He is primarily interested in applying theories of imperialism, neocolonialism, and underdevelopment to global capitalism and Canada’s role therein. Visit his website at www.owenschalk.com.