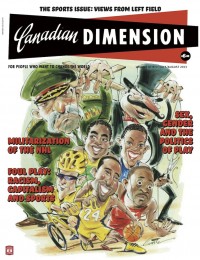

Why the Canadian Football League is the Sweden of the Sports World

Image courtesy of the Canadian Football League

In the age of sports superstars with multi-million-dollar salaries, we tend not to think of professional athletes as workers. But, like other workers, professional athletes sell their labour to capitalists in return for a wage. With fame and fortune, they may be the most peculiar proletariat capitalism has ever produced, but it is important to remember that, throughout sporting history, athletes, like other workers, have had to form trade unions to fight for decent wages, benefits, and working conditions. And, like national economies, sports leagues vary in terms of their capital-labour relations. In some leagues athletes are still without the protection of a union and are thus subject to serious exploitation. In other leagues, players have a strong voice in the direction of their league and the future of their livelihoods.

If leagues fall across the political spectrum, the Canadian Football League (CFL) can be seen as the social democracy of the sports world – a regulated market economy in which workers have a say and in which the state (which in the sporting world is the league administration or governing body) mediates between the demands of workers and capitalists, while looking out for the health of the system (or league) as a whole. Compared, for instance, to the world’s top soccer league, the ruthlessly capitalist English Premiership (EPL), the CFL is the Sweden of the sports world.

Take the issue of wage inequality. With centralized wage negotiations and other forms of market regulation, Sweden has managed to curb the gross wage inequality characteristic of free-market economies. The CFL’s salary cap, set by the league in negotiations with the players’ union and franchise owners, ensures that no team’s wage bill tops $3.8 million in the 2006 season. The result is both less wage inequality within a team and amongst players across the league. Some players make more than others, but no player is grossly overpaid at the expense of others; a form of wage solidarity if you like.

The salary cap allows the CFL’s franchises to remain competitive with one another. Compare this with the EPL, a league without a salary cap or a strong players’ union: In 2003, a Russian oil tycoon bought one of English soccer’s better teams, Chelsea. He has purchased some of the world’s best players, recently spending over $120 million on two players alone. With other rich teams like Manchester United and Liverpool spending millions in a season, the EPL has become dominated by the few, a sporting version of monopoly capitalism. In addition to wages, the benefits, pensions and working conditions of CFL players are roughly equal across the league whereas they vary widely across English soccer. Though formed over fifty years later than the English soccer players’ union, the Canadian Football Player’s Association has been considerably more militant, making sporting history in 1974 with the first strike among professional athletes in North America.

In addition, whereas English soccer players had to wait until the mid-1990s to win the right of free agency, a strong union has ensured that free agency is a feature of labour relations in the CFL since the early 1980s. And, unlike their fellow professional athletes in the EPL, players’ wages in the CFL must equal to at least fifty per cent of the League’s gross revenue. If profits increase and the players’ share of gross revenue falls below the fifty-per-cent mark, team owners are obligated to renegotiate wages, resembling Swedish social democracy at its best.

Simon Black is an Assistant Professor of Labour Studies at Brock University and Canadian Dimension’s sports columnist.

This article appeared in the September/October 2006 issue of Canadian Dimension (Good to the Last Drop).