Where’s the Green Party Going?

The last election might be viewed as the Greens’ first real kick at the can. It was the first time the party ran candidates in all federal ridings, the first time they were considered for inclusion in the leaders’ debates and the first time they garnered significant media attention. On election night, it won 4.3 per cent of the popular vote, making it eligible for public financing. Most voters look at the “green” moniker and seem to think they have a pretty good idea of what the Green Party stands for. Many Canadians assume that the Green Party of Canada is like the Green parties of Europe and the U.S. However, in their recent convention, the Canadian Greens seem to have opted to continue in a direction that is not entirely in keeping with progressive values.

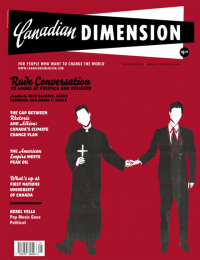

Green politics in Europe were inspired by political ecologists like Elmar Altvater and Alain Lipietz. These intellectual leaders were critical of Soviet socialism and believed that the aspirations of the workers’ movement no longer fully reflected the public’s ambitions. Their analysis was grounded in a critique of the market as well as a critique of Communism. Green politics in Europe grew from the peace, feminist and workers’ movements.

Jim Harris’s Regressive Tax Policy

The Green Party of Canada appears to stem from a different pedigree. A quick visit to the party’s website will reveal an advertisement for a conference on “environmental conservation and economic conservatism,” with Preston Manning and Fraser Institute representatives as featured speakers. In the platform, Green Party leader Jim Harris states that “in the early 1980s, I became a Conservative in reaction to the continued deficit financing by the Liberals” and discusses his shift from “fiscal conservative to ecological conservative.” The platform also includes statements such as “Lowering taxes on income is one of the best ways to support job creation” and commitments to “reduce the debt” and “adopt a strategy that uses interest rates to target inflation.”

The major plank in the Green platform is a $3.5 billion income-tax cut that will be funded through green taxes on “pollution, waste and inefficiency.” The Green Party will also “maintain the current (Liberal) plan for reducing corporate income taxes to encourage reinvestment.” The Green Party states that their policy aligns “our urge to pay less taxes” with “a more sustainable lifestyle,” but this type of reasoning is dangerous for a number of reasons. First, such a tax policy holds the potential to be quite regressive. The Green Party attempts to reduce the regressive nature of income-tax cuts by targeting them towards the lowest income-tax bracket. Under such a plan a millionaire will get the same tax break as someone earning $35,000, and the 45 per cent of Canadians who earn less than $35,000 will see their tax breaks decrease with their income. The income taxes are to be replaced by resource taxes that will increase the price of essentials like electricity and water. These utilities take up a higher percentage of lower-income individuals’ budgets, so in the end the tax policy is likely to hit the poor the hardest.

When the Green Party was criticized for regressive taxation policies during the election, it became quite defensive. In a rebuttal to a Globe & Mail article written by Murray Dobbin that was posted on the party’s website, the Green Party stated that their tax policies are progressive because higher-income individuals are more likely to “drive bigger cars, own more cars and drive longer distances.” This might be the case, but it misses the point on whether or not the taxes are progressive. A progressive tax is one that taxes the poor less than the rich as a proportion of income. Lower-income individuals most likely do use less energy than the rich, but energy costs also make up a larger percentage of their budget.

Because the Green Party does not seem to be fully cognizant of distributional issues it fails to realize that its fiscal policy might not be entirely effective. The poor might not have the ability to react to price incentives due to the high costs of investment in energy-efficiency improvements and the higher resource prices can be easily lost in the hustle and bustle of middle- and upper-income individual’s financially turbulent lives.

Another problem is that the Green plan is likely to leave the government with less revenue to invest in public goods necessary for sustainability, like transportation, energy retrofits, sewage treatment, brownfield clean-ups and national parks.

Within the Green Party’s platform you find a preference for market-based policies. For instance, its monetary policy is critical of the high rates of unemployment created by the Bank of Canada’s interest-rate policies in the early 1990s but still adopts a policy of using interest rates to curb inflation. The Greens fail to acknowledge structural changes (through industrial relations, social bargains, or more radical steps) that are necessary to achieve both high employment and low inflation.

The Green Party is inclined to use tax incentives to encourage gender and pay equity, childcare and corporate social responsibility. These market-based policies might encourage certain desirable social amenities since they become valued within markets, but it also makes the jettisoning of such amenities acceptable if they do not provide adequate economic returns. This is distinctly different from an attitude that believes that equity, childcare, a clean environment and corporate responsibility should be given to all citizens as social rights.

With the re-election of Jim Harris as leader at the party’s recent convention, the Greens seem to have opted to continue with a free-market, pro-business brand of environmentalism. Harris earns his living as a corporate motivational speaker and has supported policies of corporate self-regulation like ISO 14001. Harris sees such corporate self-regulation as a useful complement to government regulation, but the debate over ISO 14001 has aroused suspicion amongst some former Greens. Joan Russow, who defeated Mr. Harris in a previous leadership contest, says that “ISO 14001 was developed by corporations because they were afraid government might develop strong regulations…. A lot of Greens themselves don’t know how Jim Harris is catering to industry by supporting a voluntary enforcement regime.” Russow and a crowd of other activists have since quit the party. There is little evidence that the Party has been influenced by the schools of political ecology and ecological economics that emphasize that the environment is an issue best kept within the democratic sphere. These schools of thought believe that it is when citizens are engaged in forms of democratic deliberation over the needs of fellow citizens, future generations and other life forms on the planet, that the environment is valued correctly and desirable institutions are created. Democratic reform that allows for the proliferation of citizens’ assemblies and citizens’ juries that will govern local common resources, influence decision makers and allow for social learning processes is thus an important “green” reform.

Perhaps a red-Tory styled Green party will reflect a uniquely Canadian political ideology and the Green Party will flourish in subsequent elections. In the last election, the environment was an issue in large part because it was prioritized by Jack Layton, but the NDP as an organization seemed to be caught off guard by the strength of the Greens. Many progressive Canadians voted Green because they saw them as being to the left of the NDP. If less than half the Green votes had instead gone to the NDP in key ridings, the NDP would have picked up about 10 more seats. A debate between market-based and democratic forms of environmentalism should be welcomed. To participate in the debate a coherent red-green platform must be developed by the labour and environmental movements. Such a project warrants immediate attention for the sake of the environment and for the Canadian Left to remain a relevant political force.

This article appeared in the November/December 2004 issue of Canadian Dimension .