Accommodations for an Accommodating Nation

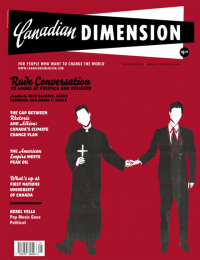

The debate in Quebec over reasonable accommodations is, in reality, one of national identity and how to both construct and integrate this young, still-evolving nation. Never before – at least in recent history – has the tension between the Canadian model of multiculturalism and Quebec’s pursuit of the intercultural model been as strong.

The Bouchard-Taylor Commission, officially a “Consultative Commis-sion on the Practices Related to Accommodating Different Cultures,” traveled through seventeen cities in Quebec between September and December, and will hand in its report in March, 2008. It must, among other things, “formulate recommendations to the government to ensure that accommodation practices conform to the values of Québec society as a pluralistic, democratic, egalitarian society.”

The points of view heard during the consultations, as well as those pronounced outside of them, were worrisome at times, flirting with racism and even xenophobia. Moreover, if the religious fundamentalism of certain immigrant communities was often denounced, Catholic fundamentalism did not miss the chance to show itself. At the same time, however, a strong sense of openness to diversity, of respect for the right to religion and the importance of equality between women and men have all been constantly expressed throughout the commission. This included the belief that the secular nature of public institutions is a necessary condition for living together.

It has been twelve years since Parizeau’s infamous “Nous,” when, on the night of the 1995 referendum, he blamed money and the “ethnic vote” for the slim loss of the Yes side – a loss we now know was due in large part to the Chrétien government breaking Quebec laws during the campaign. A majority of Francophones had clearly voted “yes,” but this wasn’t enough. They were not the only ones able to formulate the future of Quebec. The morning after the 1995 referendum, efforts were multiplied in all areas to awaken the population to issues of diversity and the need to reinvigorate efforts of integration. But the hard work of defining this new nation in all its ethno-cultural diversity ran up against the practices of Canadian multiculturalism, a multiculturalism that has always contributed to the denial of the existence of the Québécois nation.

Pauline Marois’ Project for National Identity

It is difficult for a nation that does not possess the political and judicial leverage to preserve its language, its culture, or its identity to accommodate foreigners who see their country of arrival as Canada. The Canadian constitution refuses to accommodate Quebec, and the Supreme Court has managed to reduce Bill 101 to purée, a bill whose task is to make French the official language of Quebec.

In trying to one-up Mario Dumont in the debate over national identity – an issue he has managed to exploit to the fullest – the new leader of the Parti Québécois, Pauline Marois, presented a bill on the Québécois identity to the National Assembly. The bill includes a plan to adopt a constitution and to establish a Québécois citizenship granted to Quebec residents who can prove proficiency in the French language. Only holders of this new citizenship would be eligible to run in various elections, receive financial support for political parties and to present petitions.

In turn, the Bloc Québécois will be proposing an amendment to the Canadian parliament that would protect Quebec from the federal law on multiculturalism, allowing the province to develop its own model of integration. Finally, in the hopes of reinforcing national instruments of cultural protection, the Bloc will request that all power over telecommunications matters be transferred to Quebec.

A number of columnists in the ROC (Rest of Canada) have expressed harsh words towards the Québécois, who, through the lens of reasonable accommodations, they perceive as being intolerant. But the sociological and historical conditions are very different from the rest of Canada. If it seems that multiculturalism offers a modus vivendi to Torontonians, the same cannot be said for Montreal, where the integration of ethnocultural diversity represents a key issue in the building of the Québécois nation.

This article appeared in the January/February 2008 issue of Canadian Dimension (Big Media).