No glory: One communist’s struggle in difficult times

A review of ‘James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left’

The extraordinary British radical historian Edward Thompson described one of his goals as being to spare those whose lives and dreams are lost to history from the “enormous condescension of posterity.” In writing the first half of the life of James P. Cannon, Bryan Palmer takes up an even more ambitious task. Given that Cannon later became the central figure in U.S. Trotskyism, Palmer’s task was both to spare Cannon the condescension of the mainstream and to save him from the uncritical adulation of revolutionaries who regard him as the very embodiment of “revolutionary continuity.”

Palmer succeeds on both counts. The Cannon presented here is neither doomed to marginalization nor bound for surpassing glory, but a man moving and thinking through remarkable and difficult times. Since the book ends in 1928, when Cannon was still a central leader of the Communist Party—many decades before he become identified with Trotskyism—such open-endedness is perhaps made somewhat easier.

Nonetheless, in a bold closing section Palmer assesses, mostly positively, Cannon’s whole career. In doing so, the historian validates not only the Trotskyist tradition, but also emphasizes the manner in which the factional tumult within a heterogenous radicalism was not destined to end in Stalinism. For Palmer, the figure of James Cannon intervenes in the history of Communism in way that contests ahistorical views of the movement.

The book works through two dramatic arcs. The first tells the story of how a young native of tiny Rosedale, Kansas, discovered the world and his own capacity to understand and transform it. “Jumping scales,” as radical geographers put it, Palmer places the booming Kansas City area in “a world of change.” The historian demonstrates how Cannon drew upon ideas from the Irish diaspora and his family’s own Knights of Labor and socialist past in a city in which immigrant labour mattered deeply.

James Cannon dated his own radical origins not to the Socialist Party, which he joined in 1908, but rather to his entry three years later into the ranks of the direct action-oriented, revolutionary unionism of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies).

Cannon was a talented street speaker, and his youthful rise to leadership showed the importance of direct action to the day-to-day IWW culture and dramatic agitation tactics. Cannon likened his mentorship at the hands of legendary Wobbly organizer Vincent St. John to enrolling in “The Saint’s school of learning by doing.” The phrase also applied to Cannon’s rapid development as a revolutionary unionist. He was quickly thrust into a mass strike in Akron, Ohio, and a bitter free-speech fight in Peoria, Illinois.

The Wobblies attempted to organize both footloose, itinerant “rebel workers” and married “homeguards.” In this respect, the book suggestively ties Cannon’s early marriage to his high-school teacher to his growing distance from the IWW, which he ultimately saw as the turf of single, footloose organizers. The comradeship and love of Cannon and Rose Karsner is well sketched, alongside useful provocations regarding manliness, revolutionary leadership and the ways in which women’s voices were silenced. This is clearly relevant to our ideals, even if not to early twentieth-century norms.

The second dramatic arc concerns what Palmer’s subtitle calls the “origins of an American revolutionary left,” which the historian implicitly dates from the decade after the Russian Revolution. Nonetheless, the heroism of constructing a revolutionary Left jars constantly against the realities of the 1920s: a literal decimation, at times, of its political ranks; massive repression; deportations; and fierce factional politics, characterized by sharp reversals of opinion, hinging as often upon personality as upon principle.

The blow-by-blow details of Communist politics in that decade defy treatment in a review, but it is worth remarking on Palmer’s success at showing Cannon’s centrality within them. The historian highlights how Cannon was able to maintain a level of consistency in a brutal political atmosphere.

The role of Moscow—Cannon was an early and influential United States Communist visitor in the capital of world revolution and Russian nationalism—in both creating possibilities and shutting them down is masterfully captured. Also noteworthy is the extent to which those whom Palmer calls “heartland” radicals, like William Z. Foster, Earl Browder and Cannon, with roots in the Midwest and with long, shared political histories in the IWW and syndicalist formations, effectively united and divided to shape factional alliances.

The main story of the early 1920s lay in the necessity of creating a legal “American” party, as opposed to one based in the foreign-language federations and premised on the necessity of an underground existence. As it happened, neither side of the debate—not the legal “American” forces best positioned to agitate politically, nor the foreign-language sections with the most at stake—managed an effective response to the most important political issue facing the Left in the twenties: the defense of the right to immigrate. Indeed, as the late Josephine Fowler remarks in her brilliant volume, Japanese and Chinese Immigrant Activists: Organizing in American and International Communist Movements, 1919-1933 (Rutgers, 2007), one Communist impulse was to welcome restrictive policies—in part to make for an allegedly more organizable working class.

We now know better. Palmer’s faithful, moving account of the choices Cannon faced has important lessons for us. One of those lessons is that, even as we weigh the decisions the choices and hopes of previous radical generations, we need to attend to our own imperatives and dreams.

David R. Roediger is the Foundation Distinguished Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Kansas, where he has been since the fall of 2014.

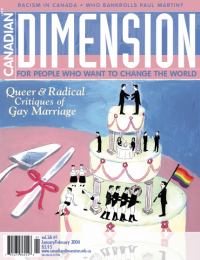

This article appeared in the May/June 2008 issue of Canadian Dimension (May Day!).