The left’s review

Most English-speaking leftists over the age of forty grew up reading the New Left Review (NLR). Founded in 1960, the journal brought together the first British New Left, which exited the Communist Party in 1956, publishing the New Reasoner, and a younger generation that put out the Universities and Left Review.

Uneasy origins

Struggling from its inception to successfully integrate quite different political sensibilities, the NLR never quite succeeded. The differences separating E.P. Thompson and Perry Anderson, for instance, have become the stuff of left legend. Few who know well enough the debates actually understand thoroughly how complicated the tensions and alignments – both political and social – were in the 1959-63 years that saw the NLR launched and reconfigured.

Anderson won the war for editorial position. By the mid-1960s, he was charting a course for the NLR that was unambiguously internationalist and theoretical. As Thompson and John Saville championed the possibilities of working-class-led socio-economic transformation and the cultural renewal of the Left in the Socialist Register, Anderson, Tom Nairn and Robin Blackburn pushed the Review in different directions.

NLR and the voice of 1968

The NLR began to introduce its readers to Walter Benjamin, Antonio Gramsci and other western Marxist thinkers. In conventional academic disciplinary terms, the Review was now less historical and more philosophical/sociological. It also dabbled in radical psychology (R.D. Laing) and offered up a little anthropology (Claude Lévi-Strauss). Most importantly, Cuba, China and struggles in the Third World animated the pages of NLR as much as events in Great Britain, the U.S., or Europe.

All this fit well with the New Left temper of 1967-68. The carnage in Vietnam unleashed a youthful anti-imperialist revolt. This in turn created a sense that, for the first time since the 1930s, Revolution might be in the political cards. Black Power’s uprising in America, the May events of the barricaded Parisian Left Bank, the anti-Stalinist Prague Spring and the ongoing Maoist Cultural Revolution fueled an optimism of the will that fired transformative expectations.

Downturn: The massacre of the ancestors

By 1974, all this and more had passed. Marxism was in crisis; capitalism was ideologically ascendant. Many of the NLR’s beacons of radical thought no longer shone brightly.

In the words of Anderson, “the massacre of ancestors” had been “impressive.” Jean-Paul Sartre, arguably France’s leading gauchiste in the 1960s and a champion of struggles from Algeria to Asia, was now, in Anderson’s judgment, a “disabled anarchist.” Lucio Colletti, so favoured by the NLR in the early 1970s for his science and logic of Marxist analytics, was a decade later little more than an “embittered liberal,” while the philosopher Andre Glucksmann decamped to the New Right. Nicos Poulantzas committed suicide in 1979, and Louis Althusser, succumbing to a psychotic break that culminated in him strangling his wife in 1980, was institutionalized.

Pessimism of the intellect

The NLR retrenched into a pessimism of the intellect. Its articles, over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, offered an often unsurpassed critique of the escalating nuclear arms race and the collapse of Stalinism. With the fall of Communism, the Review was swept along in a torrent of left commentary on Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history.” Robert Brenner’s overviews of capital’s post-World War II restructuring spoke tellingly of what NLR could still provide.

But Marxism and the revolutionary Left are necessarily captive of certain deformations when no mass movement animates a sense of social transformation’s possibilities. The NLR was pushed and pressured by the rising political tides of the neoliberal Right. In tandem, it was constrained by the receding politico-intellectual hairline of the Left, which in an age of Stalinist collapse showed few signs of new Marxist growth. Anderson and the NLR seemed to have less and less of the revolutionary resolve that had characterized their earlier project. To many, a New Left journal seemed to be growing old and tired.

The price of political exhaustion

One measure of this was a seemingly never-ending set of factional eruptions. They produced an exodus from the NLR of editorial board members and writers. Such splits often left a wake of acrimony and allegation. More critically, after forty years and 238 issues, Anderson launched a new series of the NLR in 2000.

The new series was prompted by what Anderson dubbed the “conjuncture of ‘89.” Stalinism’s failure and the uncontested consolidation of neoliberalism’s capitalist hegemony, according to Anderson, rewrote the script of what it was possible for the NLR to accomplish. In the name of realistic appraisal, Anderson was charting a new direction for the Review. It was one that would refuse to understate the nature of capital’s victory. Many denounced the new turn as an abandoning of left analysis and an embrace of liberal pluralism, among them longstanding contributors and former editors like James Petras, Boris Kagarlitsky and Ellen Wood.

Reading the Review’s record

Duncan Thompson’s Pessimism of the Intellect? A History of the New Left Review (Merlin Press, 2007) looks back on the NLR’s history, suggesting that Anderson’s 2000 turn was premised on a flawed overstatement of neoliberalism’s triumph. It assesses the NLR’s complex history with verve and insight.

Even close readers of the Review can learn much of what was happening at specific times and within particular political conjunctures. Thompson provides, for instance, an illuminating glimpse of how quickly, even mercurially, Anderson and his allies moved from Maoism to a somewhat unstable embrace of Trotskyism in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Still, this is an overview that is untroubled by the deep complexities of an inaccessible archive. Anderson holds the keys, largely, to the vaults in which correspondence and the record of relations among NLR editors, supporters and writers is stored. He is unlikely to open up these files to anyone, just yet. Until that happens, Thompson’s brief, informed and articulate book is as good a place as any to review the Review.

This should be something that younger leftists, in Canada and elsewhere, who did not come to their current politics with copies of NLR piled on their shelves, undertake. For, whatever one’s political convictions, the thinkers and activists who figured prominently in the NLR are all worth engaging with. Anderson himself, whatever the direction in which he guided the NLR, is often a brilliantly critical mind, awe-inspiring in his intellectual reach. In keeping alive a publication like the NLR for almost half a century, Anderson, Blackburn and others have earned a justifiable respect from all of those inhabiting the space where the Left lives and thinks.

Bryan D. Palmer is the author of Revolutionary Teamsters: The Minneapolis Truckers’ Strikes of 1934 (Chicago: Haymarket, 2014) and a past editor of the journal, Labour/Le Travail. He is the Canada Research Chair, Canadian Studies Department, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario.

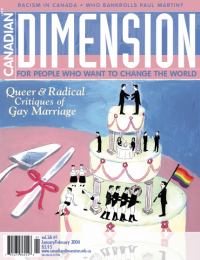

This article appeared in the November/December 2008 issue of Canadian Dimension .

.png)